No hea koe? No Taamaki Makaurau au

Photo Credit

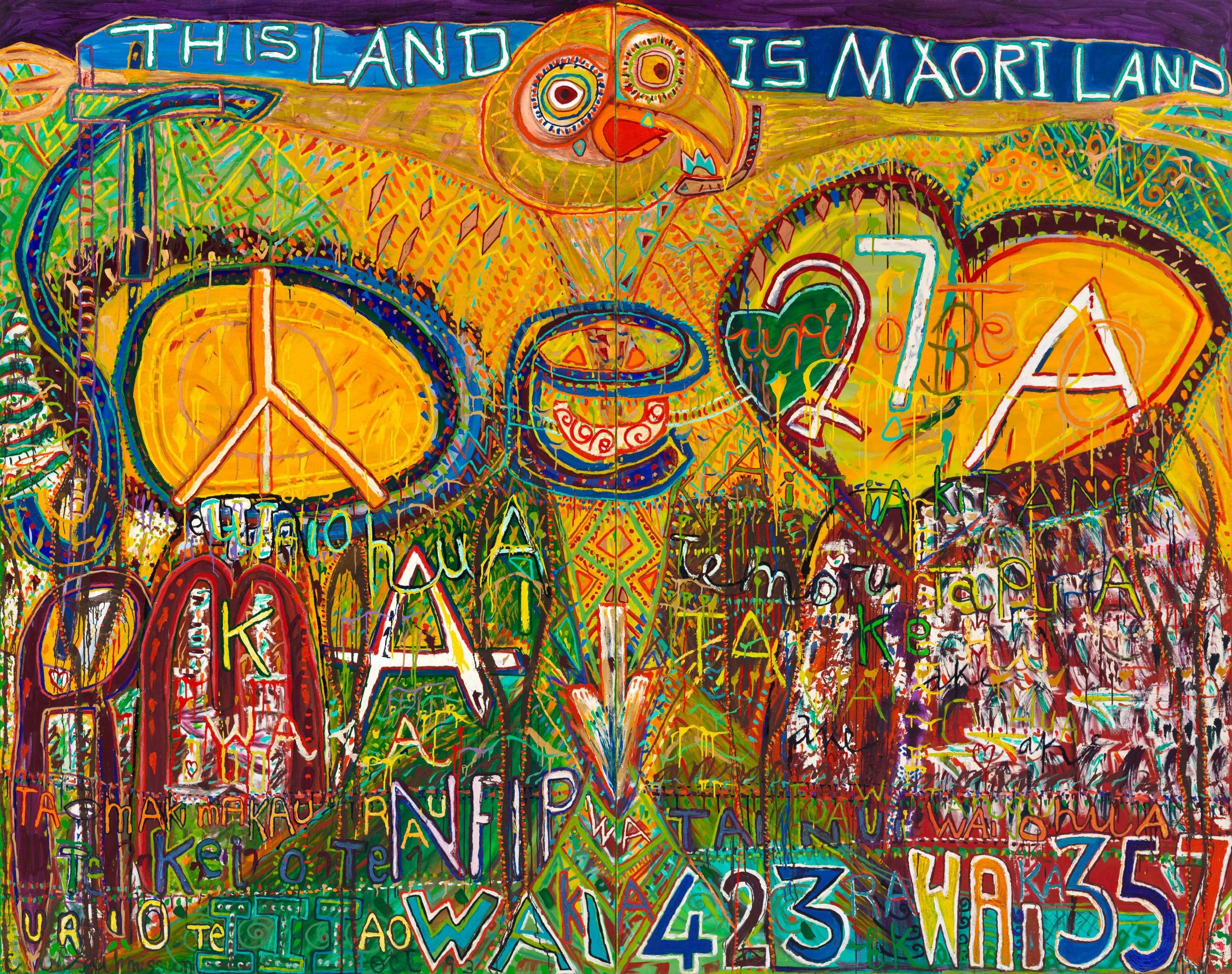

Te Uri O Te Ao, 1995, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased with the assistance of Reader's Digest New Zealand Limited, 1997.

Hana Pera Aoake

Jul 06 2021

The first work by Emily Karaka that I ever saw was ‘Te Uri O Te Ao’ (1995) at the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. A Ruru looks out from the painting with the words ‘This land is Māori land’ inscribed on it. The Ruru acts as a kaitiaki with arms outstretched like a korowai. The cries of the Ruru perhaps signal Karaka’s own passionate karanga against Paakehaa oppression of Maaori. (1) There is a cross there too: a symbol of worship and an indictment of broken Paakehaa promises. (2) The frustration and sadness in this work is still felt twenty-six years after its making. The paint drips in a flurry, bleeding down the canvas, and frenetically zooming across the pictorial plane. At the time of its production, Karaka was involved in a Treaty of Waitangi claim for her hapuu, Ngaai Tai ki Taamaki, represented by the words ‘WAI 423’ and ‘WAI 357’ at the bottom of the canvas.

In Korurangi: New Māori Art (1995), curated by George Hubbard at the Auckland City Art Gallery (now the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki), ‘Te Uri o Te Ao’ was hung behind ‘Flagging the Future: Te Kiritangata - The Last Palisade’ (1995) by Diane Prince (Ngaati Whaatua, Ngaa Puhi). Both works criticised the Crown’s confiscation of Maaori land. ‘Te Uri o Te Ao’, in asserting ‘This land is Māori land’, critiques the government’s raupatu policies and privatisation of our whenua. It is a reminder that we are on Maaori land and the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki stands on whenua connected to Ngaai Tai ki Tamaaki, to which Karaka has whakapapa ties. In one example of the mana Karaka wields, and the challenge her work poses to certain sections of privileged Paakehaa society, the conservative National Party MP Ross Meurant, in 1987, accused Karaka of being a terrorist intent on overthrowing the New Zealand government, to which she replied: ‘I am armed with a paint brush. If that is regarded as terrorism, then I am a terrorist. My artwork is my platform. My work is my patu.’ (3)

Karaka is a senior Maaori artist with whakapapa ties to Ngaai Tai ki Taamaki, Te Kawerau aa Maki, Ngaati Tamaoho, Te Aakitai Waiohua, Te Ahiwaru, Ngaati Mahuta, and Ngaati Tahinga (Waikato/Tainui), and Ngaati Hine (Ngaapuhi). Karaka’s paintings tell the stories of Taamaki Makaurau and help us understand the geography of a city that is embedded within her whakapapa all over the isthmus. For Maaori when we ask No hea koe?, it is a question of relating not only to where and to whom you whakapapa, but also where geographically on the whenua are you from. Geography is whakapapa, and so many sites across Taamaki Makaurau are places Karaka can call her tuurangawaewae, a place to stand, to karanga to spaces between the past and present so she can look to the future. Over the last almost-thirty years, she has worked for her iwi Ngaai Tai ki Tamaaki addressing their environmental and political concerns through her art and Waitangi claims. This theme of whakapapa has been the puaawaitanga of not only her political work, but also her art practice which she has exhibited for more than forty years.

Photo Credit

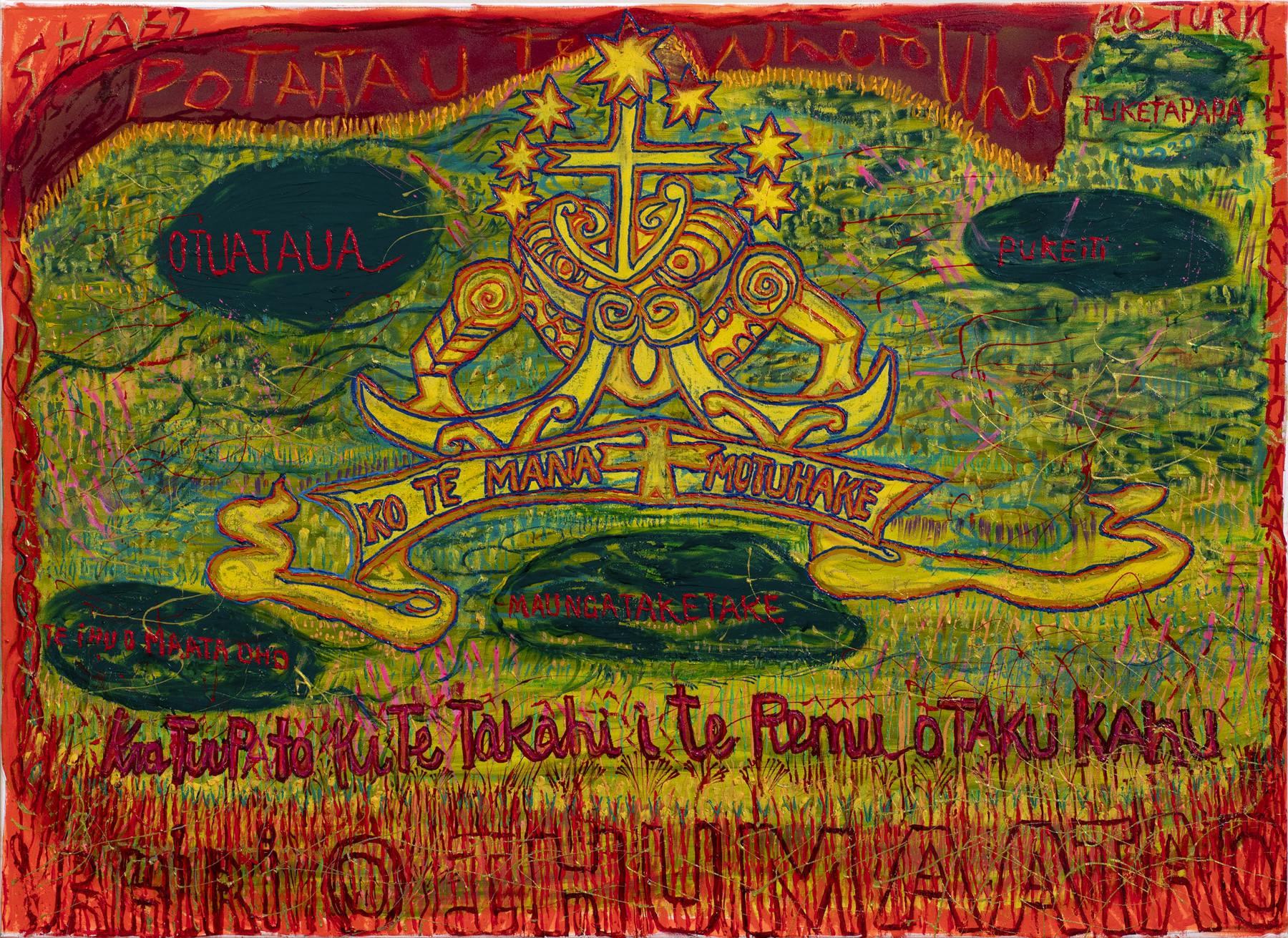

Riri at Ihumaatao (Anger at Ihumaatao), 2020, courtesy of the artist and Visions gallery.

"I am armed with a paint brush. If that is regarded as terrorism, then I am a terrorist. My artwork is my platform. My work is my patu."

IN AN INTERVIEW, Karaka states that, ‘Pootatau Te Wherowhero [the first Maaori king] warned, ‘Beware the rim of my cloak.’ And the rim of his cloak is the Tāmaki area. It’s also called ‘Te Kei o Te Waka o Tainui’ [the Stern of the Tainui Waka].’ (4) It was this connection that led her to develop the work shown at NIRIN (2020), as part of the Sydney Biennale. In this body of paintings, Karaka focused on the laws and historical confiscations of land enacted by the Crown at Ihumaatao where Pootatau Te Wherowhero was crowned. Karaka focused not only on the relationship the Kiingitanga has to Ihumaatao, but also her own whakapapa to Puketaapapa and Ihumaatao, as a descendant of Te Arawaru Toone. In ‘Riri at Ihumaatao (Anger at Ihumaatao)’ (2020) we see Pootatau Te Wherowhero’s name written at the top, with the Kingiitanga flag in the centre and the waahi tapu stonefields dotted throughout. Karaka is educating us on the history and geography of Taamaki Makaurau.

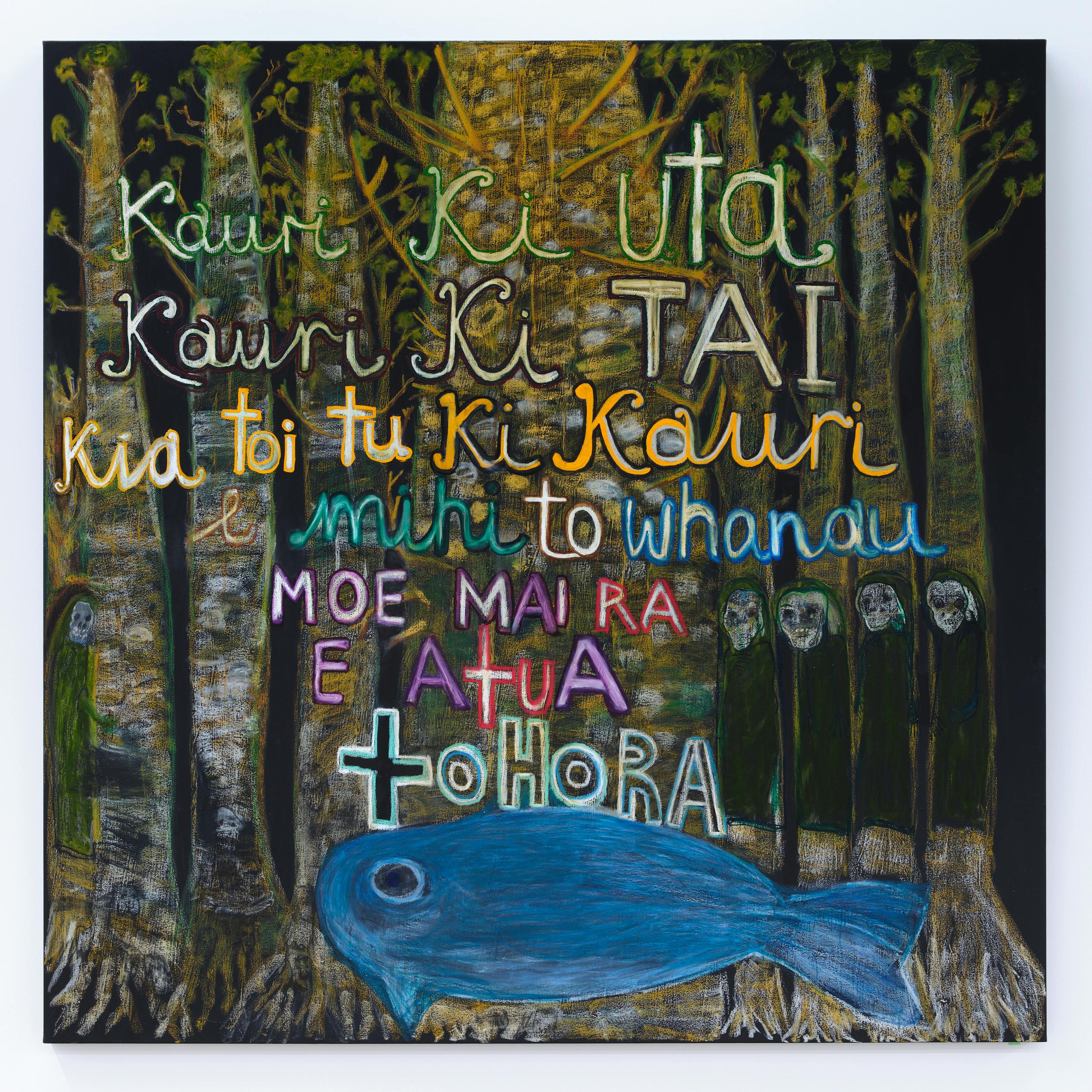

In another recent body of work, ‘CULTURAL ID; Marae, Maunga, Motu’ exhibited in Toi Tū Toi Ora, curated by Nigel Borell at Toi o Tāmaki, Karaka explicitly outlines the whakapapa of the land around Taamaki Makaurau. Three large paintings depict and map the maunga, marae and motu or surrounding whenua of Taamaki Makaurau. These are accompanied by a selection of stones from Motutapu island running along the north atrium’s large plinth-like balustrade. In ‘Maunga’ (2020) we see this island and a map with red lines directing us to all of the sacred maunga, with a whai, or stingray, acting as a kaitiaki of the Hauraki Gulf and Manukau Harbour. ‘Marae’ (2020) is a purple map marking significant Tainui/Waikato marae across the whenua. ‘Motu’ (2020) is a painting of Uenuku, the sacred Tainui taonga held at Te Awamutu Museum. Our greatest and most mysterious taonga is said to contain the spirit of rainbow atua, Uenuku, which came to Aotearoa on the Tainui waka. This taonga appeared in ‘Motutapu’ (2015) from Karaka’s Settlement series, which also features a cross, and a white flag with the Matariki constellation. These are all symbols relating to Mahuta Taawhiao Pootatau Te Wherowhero I’s flag, (5) which is one of a number of flags still used at the poukai, an annual series of visits to marae affiliated with the Kiingitanga, and at koroneihana, or coronation, celebrations. In 'Motu', Karaka’s Uenuku is bright red and appears to be floating on a waka with the names of important places, hapuu and iwi of Taamaki Makaurau. While this work speaks strongly to Karaka’s specific whakapapa it includes the many different tribal groups who have claims to this place. The words ‘Ake, ake, ake’, which can translate roughly as ‘affirm, affirm, affirm’ spindle down the body of Uenuku. Karaka is well known for her use of language, utilising both te reo Maaori and English. 'Words are trade exchange,' as she has previously noted. 'When you are living in an urban Maaori context you are bombarded by propaganda words everywhere—billboards, shops, the written language is there.’ (6)

Photo Credit

CULTURAL ID; Marae, Maunga, Motu, 2020, courtesy of the artist and Visions gallery.

The impact of each painting’s scale is emotional. It is one way in which many Maaori were able to see themselves in Toi Tū Toi Ora, an experience I had seeing a number of my marae. Karaka’s decision to make these markings was to acknowledge not only her own whakapapa, but the enduring importance of Kiingitanga marae and Te Whakakitenga, the parliament. The artist’s father, John Mita Karaka, was named after his great grandfather Mita Karaka, who went to England on a delegation with Te Rata Mahuta Pootatau Te Wherowhero, the Maaori King, to address Treaty of Waitangi concerns with the British Crown in 1914.

A common saying amongst Tainui/Waikato when describing our rohe is,

Ko Mookau ki runga Ko Taamaki ki raro Ko Mangatoatoa ki waenganui. Pare Hauraki, Pare Waikato Te Kaokaoroa-o-Paatetere.

Mookau is above Taamaki is below Mangatoatoa is between. The boundaries of Hauraki, the boundaries of Waikato To the place called ‘the long armpit of Paatetere’.

Photo Credit

Pandemic, 2021, courtesy of the artist and Visions gallery. Image by Sam Hartnett.

The impact of each painting’s scale is emotional. It is one way in which many Maaori were able to see themselves in Toi Tū Toi Ora, an experience I had seeing a number of my marae.

IN 1979, while Colin McCahon was teaching at Outreach (now Studio One Toi Tū) he visited Karaka’s first solo exhibition. (7) ‘Colin stood in front of my work ‘In the Mixing Bowl’ and said he particularly liked the cadmium yellow background, that I showed skill, and could make a career in painting,’ Karaka recalls. (8) Earlier this year from February to April, Karaka took on a residency at McCahon’s former home, now McCahon House, at Parehuia in Titirangi. Parehuia is made all the more significant for having its name bestowed in 2009 by the late kaumaatua Eru Thompson, a tuupuna of Te Kawerau aa Maki (9) (an iwi to which Karaka can trace her whakapapa). It was here that Karaka produced her most recent body of work, Rāhui.

Raahui is a form of tapu that restricts or prohibits access to or use of a particular area, body of water or resource. It is enforced by those with the mana or authority to do so. Often it is a means of conservation, but it can also be asserted after a death as a marker of respect, or as a measure to protect the health of the people. While a raahui is not legally binding under common law, it is a form of asserting rangatiratanga. For instance the raahui imposed in 2017 by Te Kawerau aa Maki to save the Kauri trees surrounding Parehuia on the edge of Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa was largely ignored by trampers, until the Auckland City Council were pressured to enact their restriction powers under the Waitākere Ranges Heritage Area Act 2008. This has, indirectly, allowed the raahui to come into effect under an Act of Parliament. Kauri dieback (Phytophthora agathidicida), is a fatal pathogen for which there is no known cure. Of the one percent of Kauri forests that survived colonial deforestation, one in five is now infected with the disease, which severs access to nutrients and water. From 1820 to as late as 1971 there was a mass felling and milling of Kauri decimating their population, now exacerbated by the tree-destroying pathogen. For Karaka this is devastating. Kauri are atua and tuupuna.

In the first month of Karaka’s residency at Parehuia, Taamaki Makaurau went into lockdown after three community Covid-19 cases were discovered in South Auckland. Many Maaori were calling this state of prohibition raahui and Karaka saw the connection between the respective responses to Kauri dieback and the Coronavirus. In ‘Pandemic’ (2021), the compound structures for novel coronavirus, Kauri dieback, and myrtle rust are shaped like Mataaho’s bowl, Maungawhau. A round spiky formation appears to be dripping blood. Its spikes recall a microscopic view of Covid-19, and the Latin origins of the word ‘corona’ meaning crown or wreath, translated as ‘mate karauna’, or ‘crown death’—pointing to the broken Paakehaa promises to Maaori. Against a backdrop of ominous reds, a white corpse-like Kauri infects other trees with dieback spores and the two become entangled in this oval shape. In ‘Rāhui’ (triptych) (2021) we see the fraying edges of each work, the two smaller works on either side of a longer rectangular portrait, each depicting a pair of kuia embracing, both wearing korowai made of Kauri leaves. These leaves act as roimata or tears of the Kauri blighted by dieback spores. There is something bodily about each painting when viewed in person, in its full depth and texture.

Photo Credit

I Can’t Breathe, 2021, courtesy of the artist and Visions gallery. Image by Sam Hartnett.

Many Maaori were calling this state of prohibition raahui and Karaka saw the connection between the respective responses to Kauri dieback and the Coronavirus.

KARAKA'S RECENT WORK has been mindful of the potential for international solidarity. ‘I Can’t Breathe’ (2021), refers to a cry made by several African American men, including Eric Garner and George Floyd, while dying at the hands of police officers—a reference to the solidarity that Maaori have with other marginalised people and their struggles for sovereignty. The work made me reflect on Aotearoa’s own statistics around police brutality, and a criminal injustice system which has made Maaori women the most incarcerated Indigenous women in the world. It is also telling that the area in New Zealand with the most prisons is on Karaka’s Tainui/Waikato lands, which seems to be a deliberate strategy of the Crown given the resistance mounted by our Kingiitanga tuupuna in the nineteenth century.

In ‘I Can’t Breathe’ a mother, father and child crouch in front of a set of lungs with a skeleton on top of it and the words ‘I can’t breathe’. These are the lungs of Te Wao-nui-a-Tiriwa, the Waaitakere ranges, the lungs of Taamaki Makaurau. Here Karaka is making connections between racist police violence on behalf of the state and the colonial violence that has resulted in degradation of the whenua. ‘I Can’t Breathe’ also speaks in unison with ‘Te Wao nui-a-Tiriwa; Kauri Can’t Breathe’ (2021). Behind, and in contrast to, the brilliant patches of colour used to depict the lungs of Te Wao-nui-a-Tiriwa is a pool of darkness. One side of the lungs bears Covid-related text and symbols. The other side is inscribed with a biblical inscription from Isaiah 26:20: ‘Come, my people, enter thou thy chambers, and shut thy doors about thee: hide thyself as it were for just a moment, until the indignation be overpast.’ A reference to this passage is repeated in ‘3 of the team of 5 million; Do not enter’ (diptych) (2021). This passage reflects the process of overcoming the devastation of Covid-19 and the destruction of Kauri. It also calls to mind the work of McCahon who, throughout his oeuvre, used biblical passages. Another example of Karaka’s reference to McCahon and Christianity is ‘The Treaties’ (1984), which consists of three panels that each feature a crucified figure and three separate deeds, including Te Tiriti (1840), Anzus Defence Pact (1951) between Australia, New Zealand, and the US, and the Gleneagles Agreement (1977) opposing sporting contact with apartheid-era South Africa (1977).

At first glance, this might be considered work ‘of its moment’, but from a deeper vantage point Karaka is examining issues that are timeless—land, its taking, and the degradations that happen to people upon it. For Karaka stories come out from paintings because like land and people, they have a mauri. ‘Our culture has grown and grown; I don’t believe it’s static. I mean, it is a timeless knowledge so it belongs in the past, the present, and the future—so it must have the capacity to move,’ as she stated in 2002. (10) ‘Rangitoto Eruption’ (1988) is an example of this ability to shift between time. It speaks to both the eruption of Rangitoto, witnessed in 1400 by Tuupuna, and to the reclamation of Takaparawhau, or Bastion Point, in the 1970s. Rangitoto is the maunga tapu, or sacred mountain, of Ngaati Whaatua and other iwi. ‘Rangitoto Eruption’ depicts this ancient tuupuna in a defiant haka stance and celebrates the return of Takaparawhau to tangata whenua on Ooraakei peninsula.

Photo Credit

Moe Mai Raa, Tohoraa, 2021, courtesy of the artist and Visions gallery. Image by Sam Hartnett.

At first glance, this might be considered work ‘of its moment’, but from a deeper vantage point Karaka is examining issues that are timeless—land, its taking, and the degradations that happen to people upon it.

IN TE AO MAAORI, Kauri and Tohoraa, or whales, are brothers. Tohoraa once walked the land alongside his brother. Eventually he grew tired of iwi hunting him. He suggested to his brother that they hide in the whare of their uncle, Tangaroa, the ocean. But Kauri was too deeply rooted to leave the land and loved being with his kuia, Papatuuaanuku. It was then that Kauri’s brother, Tohoraa, gave him a cloak made from his skin for protection. Tohoraa missed his brother and would spout water up to Ranginui, hoping his longing would be carried by Taawhirimaatea in the winds. Eventually his younger brother grew tall enough to see him in the sea. Iwi began to cut down Kauri and use his flesh to build waka. Seeing his brother, Tohoraa rushed to him excitedly only to be attacked by humans. Not long after this he saw his brother being attacked again, so Tohoraa gave his body as a sacrifice; unable to walk on the shore to protect him, he was speared and killed. Maaori took his skin, like Kauri took his skin. Tohoraa gave his body to Maaori as a way to protect Kauri and remind them to care for him as he purifies the air and allows the deceased to embrace Papatuuaanuku.

This story is reflected in Karaka’s ‘Moe Mai Raa, Tohoraa’ (2021). A whale in the foreground is surrounded by sick Kauri trees covered in spores and grim reapers. This painting is like a tangi, with the text as a eulogy telling the Tohoraa they can enter the world of Te Poo. Aotearoa is the whale stranding capital of the world (11)—it is a chilling reminder that the felling of Kauri and the colonial hunting of whales decimated ninety-six percent of both populations. (12) Since 1840 there have been five thousand recorded incidents of whale stranding, with an average of three hundred whales stranding themselves each year. (13) For Maaori, this is a direct link between the strandings of whales and the crisis of the dieback disease killing Kauri trees, because the two are brothers by whakapapa.

Not unlike ‘Te Uri o Te Ao’ (1995), Karaka has always sought to assert the whakapapa of Taamaki Makaurau and share her knowledge of the histories, their names and the ongoing struggle for sovereignty that has shaped this city. Her use of stones gathered from the sacred Ngaai Tai ki Taamaki Motutapu island in ‘CULTURAL ID; Marae, Maunga, Motu’ acknowledges the work still to be done, the ahi kaa of continuous occupation and the raupatu whenua we all stand on. After all, this is Maaori land. Politics is life, it is the continuation of the work of our tuupuna and Karaka has sustained a decades-long career because it is her duty. ‘As mana whenua we have a spiritual obligation to protect the land. I try to depict my own view of abundance and sustainability contrasted with man’s inhumanity to his earth mother and each other.’ (14)

NB: With the exception of quotations and titles, which have retained their original spelling, Tainui/Waikato spelling of words in te reo rangatira has been used throughout to acknowledge the writer's and the artist's Tainui/Waikato whakapapa. This usage, in place of standardised te reo Maaori, which uses macrons, also acknowledges the variations in the language across different hapuu and iwi.

Endnotes:

(1) Jahnke, Robert and Witi Ihimaera, ‘The Whenua: The Land,’ in Mataora: The Living Face: Contemporary Māori Art. Witi Ihimaera, Sandy Adsett and Cliff Whiting (eds.), Auckland: David Bateman Ltd., 1996, 88.

(2) Ihimaera, Witi, ‘Earth Goddess,’ catalogue essay for Emily Karaka’s Waharoa o Ngai Tai, Auckland: Fisher Gallery, 1997.

(3) Jahnke and Ihimaera, ‘The Whenua: The Land,’ 88.

(4) McWhannell, Francis, ‘On a bright green island: An interview with Emily Karaka,’ The Art Paper, 21 April 2021.

(5) The son of Taawhiao Tuukaaroto Matutaera Pootatau Te Wherowhero, and the third Maaori King, reigning from 1894 to 1912.

(6) Gifford, Adam, ‘Finding Touchstones,’ The Weekend Herald, 22 February 2014, 8.

(7) McWhannell, On a bright green island: An interview with Emily Karaka.

(8) Karaka, Emily, ‘Tangi. Muriwai,’ McCahon 100.

(9) McWhannell, Francis, ‘I bow my head: Emily Karaka’s Rāhui,’ catalogue essay for Rāhui by Emily Karaka, Visions gallery, 2021.

(10) Tamati-Quennell, Megan, ‘Emily Karaka: in conversation with Megan Tamati-Quennell,’ in Taiāwhio: Conversations with Māori Artists. Huhana Smith, Oriwa Solomon, Awhina Tamarapa, Megan Tamati-Quennell and John Walsh (eds.) Wellington: Te Papa Press, 2002, 94.

(11) Ainge Roy, Eleanor, ‘What is the sea telling us? Māori tribes fearful over whale strandings,’ The Guardian, Monday 26 November, 2018.

(12) Kerridge, Donna, ‘What we can learn from the stories of Kauri, Tohorā and Tiwaiwaka,’ The Spinoff, December 3, 2020.

(13) Ainge Roy, Eleanor, ‘What is the sea telling us? Māori tribes fearful over whale strandings.’

(14) White, Jillian, ‘Art show features culture,’ Ngā Korero o te wā News. Auckland: Te Māori News, 5 November 1997.

About the Author

Hana Pera Aoake (Ngaati Hinerangi me Ngaati Raukawa, Ngaati Mahuta, Tainui/Waikato, Ngaati Waewae, Kaati Mamoe, Waitaha) is an artist and writer based in Te Wai Pounamu. Hana published their first book, A bathful of kawakawa and hot water, in 2020 with Compound Press. Hana holds an MFA in Fine Art from Massey University (2018) and was a participant in the ISP programme at Maumaus des escola artes (2020). Currently, Hana is involved in Regional Assembly, an artist-led online studio programme connecting cultural practitioners working in regional and remote geographies across the Asia-Pacific and co-organises Kei te pai press with Morgan Godfery (Ngaati Awa, Ngaati Maniapoto, Lalomanu, Vailima, Ngaati Tuuwharetoa, Ngaai Tuuhoe).

ArtNow Essays is independently commissioned by the editor. The views expressed on ArtNow Essays are the authors' and are not necessarily held by ArtNow.NZ, the commissioning editor, editorial advisory, participating galleries, APGDN, or Creative New Zealand. While this platform does not publish readers’ comments, constructive feedback is welcome. Send your feedback to essays@artnow.nz.