Bedroom Diaries

Photo Credit

Installation View, 'I Think You Like Me But I’ve Been Wrong About These Things Before,' Natasha Matila-Smith, Artspace Aotearoa, 2021. Image courtesy of Sam Hartnett.

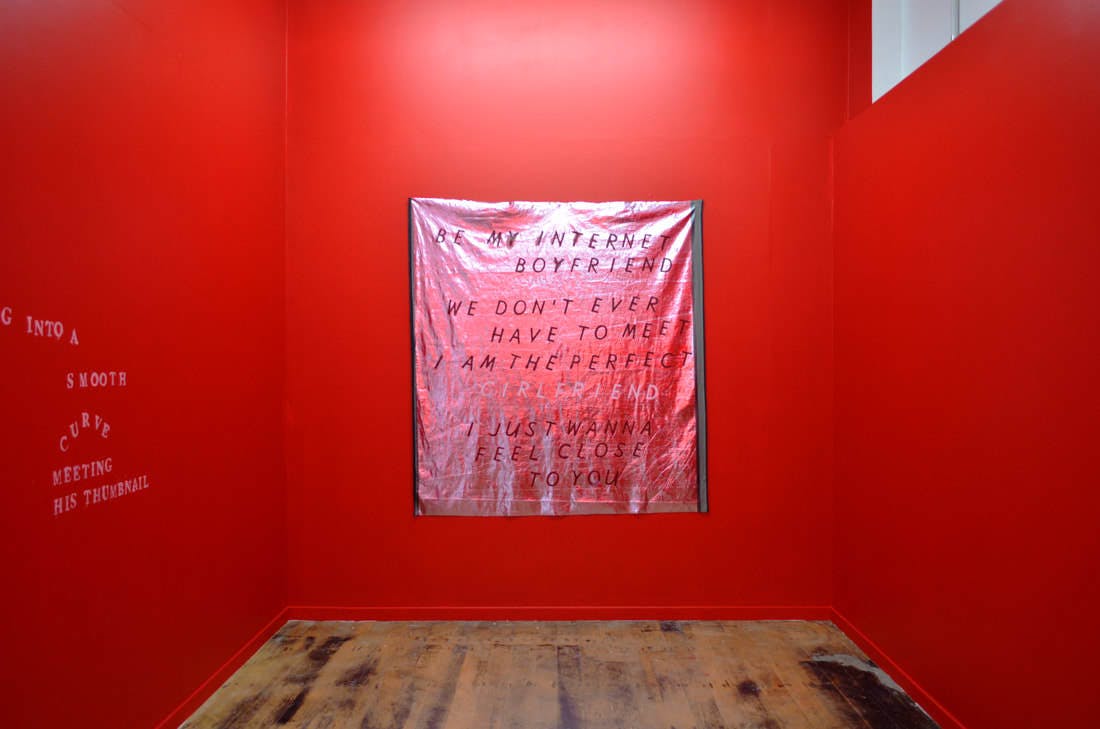

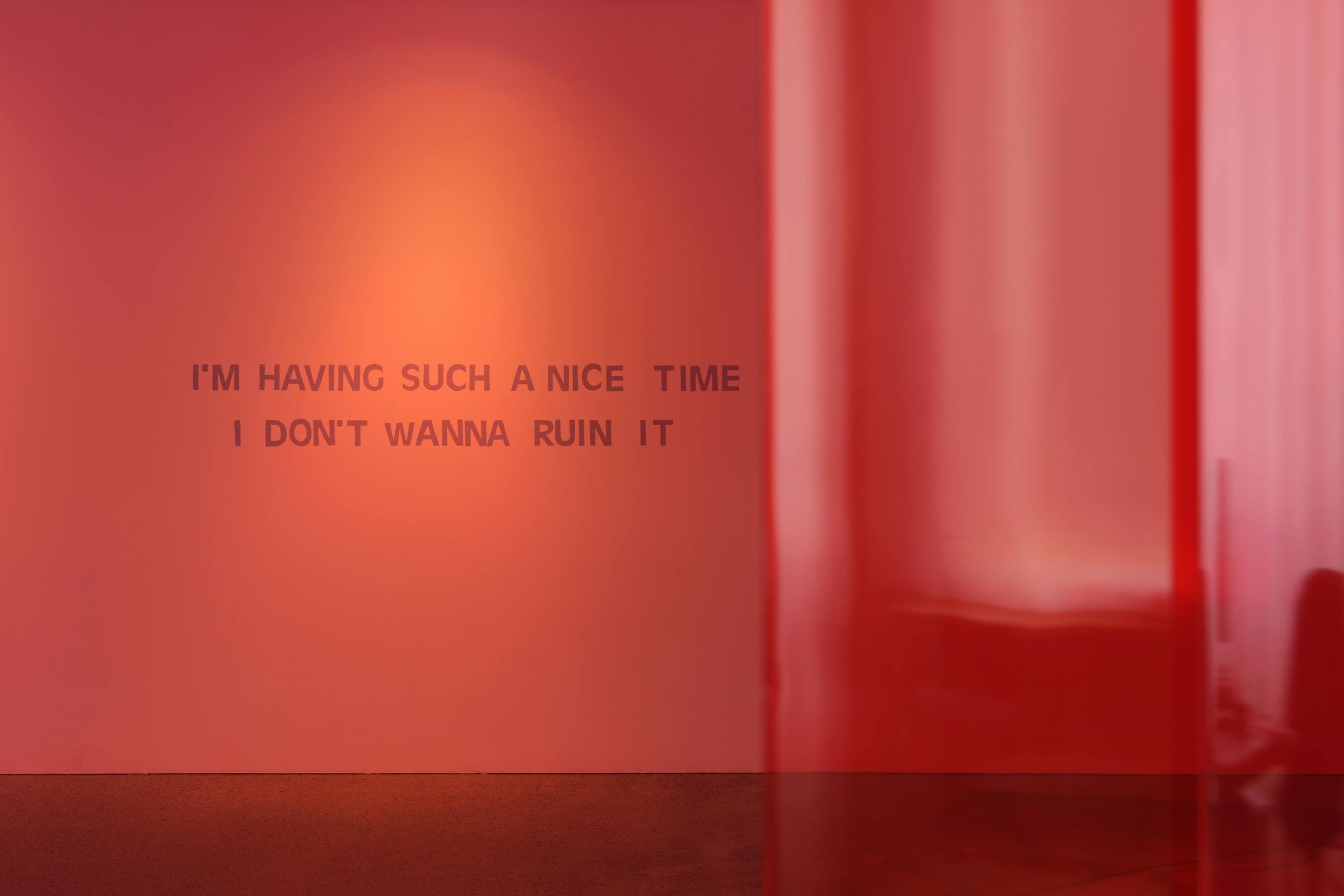

THE FIRST THING YOU NOTICE are the floor-length red plastic blinds, at once sexy and off-putting. You walk through a gap in them to reach the exhibition proper. I think of bare thighs peeling off vinyl-covered banquettes. Cropped images of different parts of the artist’s body, her thighs among them, flirtatious little snaps blown up into large, pixelated stickers affixed to the gallery walls. A mirror selfie with the face cropped out, her free hand pulling up her skirt to show a wink of thigh above black stockings. Hand-painted on the wall next to this image reads the slogan: I’m much more fragile than I appear. Here is a paradox in posting pictures of your semi-clad body online: the desire to incite lust against the desire to be handled gently. For her solo exhibition at Artspace Aotearoa, ‘I Think You Like Me But I’ve Been Wrong About These Things Before,’ Natasha Matila-Smith (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Hine, Sale'aumua, Pākehā) presents the parts of her body she prefers alongside feelings no one is supposed to verbalise, at least not in public. But this exhibition isn’t public, not really. This exhibition is her bedroom.

Matila-Smith is an artist known for her bedroom works, as I like to think of them—works that share the softness of sheets and the vulnerabilities we wallow in beneath them. Works that make the viewer feel as though they know her, because here are her feelings, spelled out for us in poetry on velvet, cotton, vinyl:

‘Be my internet / boyfriend’

‘I’m not asleep but I’m not entirely awake either’

‘Unrequited / feelings / is it only / me getting to / experience the heartache’

‘I cry coz I know / you’re too / good / for me’

‘Love me?'

Yet for all her soul-baring, through her art and her internet presence, Matila-Smith is the first to admit she is shy. This makes an idiosyncratic kind of sense. For many of us, connecting through screens from the comfort and safety of our homes is easier than meeting in the flesh. And, unsurprisingly, her primary material is text: secret weapon of the self-conscious because the written word is malleable, easy to hide behind. Its affect can be confessional without revealing much. In an interview with Cityscape, Matila-Smith explains how ‘it shocks people sometimes when I write things that they would consider to be vulnerable, but I wouldn’t necessarily.’ Her works, she reminds us, ‘are curated and … they are active storytelling tools.’

Photo Credit

Installation View, 'I Think You Like Me But I’ve Been Wrong About These Things Before,' Natasha Matila-Smith, Artspace Aotearoa, 2021. Image courtesy of Sam Hartnett.

Matila-Smith is an artist known for her bedroom works, as I like to think of them—works that share the softness of sheets and the vulnerabilities we wallow in beneath them.

WHEN I THINK OF MATILA-SMITH’S WORK. I think of the French artist Sophie Calle. As it turns out, so does Matila-Smith. In a text for Enjoy Contemporary Art Space’s Occasional Journal (2018)], she writes: ‘In Suite Vénitienne, 1980, [Calle] follows a man for twelve days. I have done similar things, though never for art.’ But she has done similar things for art. Not following a man for days, perhaps, but recording her actions, using text, photography, and video to convey longing, obsession, depression, ennui. Included in Matila-Smith’s 2018 exhibition ‘If You Miss Me, Let Me Know’ at MEANWHILE in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington was a text printed on purple paper. In quintessential sad-girl style, the work was titled Manuscript for a book about how alone I am. The text, written in Matila-Smith’s distinctively deadpan voice, tells the story of an opening for a group exhibition she was part of in Australia, where she talked, drunkenly, to a boy who once ‘loved’ a photo of her on Facebook.

For a brief moment, we are close enough for it to seem weirdly intimate that two strangers are in such close proximity. I have a feeling he’s uncomfortable with this closeness and for a moment I let it make me feel ugly. As if … I’m trying to trick him into being close.

For Calle’s first work, The Sleepers (1979), she invited people into her bed, feeding them and photographing them every hour, keeping notes of their actions. Some were friends or acquaintances, others were strangers. At this point, she didn’t think of the project as an artwork; it was more of a game. I’ve always loved this work, or really any work about the public exposure of private lives, because all I really want from art is to be shown how other people live. Matila-Smith is an artist in this vein, but unlike Calle, she doesn’t need games to structure her revelations. She is a millennial; her self-revelations are seamless, easy to read for an audience weaned on oversharing. Unlike Calle, Matila-Smith came of age in a world where privacy was already under siege. When I see her photographs stuck to the gallery walls at Artspace, I read them immediately as selfies, probably taken on an older model iPhone with a crack in the screen (like my own). The awkward angles, the particular way they are cropped to cut out a face washed out by bathroom lighting, or to fill the screen with cleavage and cleavage only. Yet these are not images emerging organically without artistic license, as the artist explains:

I typically [make work] about my experiences and there is usually an aspect of questioning the reality of this account, whether it is how it really happened or just a matter of skewed perspective, or even fictionalised [perspective]. As a maker, I think of myself as an actor while making. So, while I’m making, I might be somewhat removed from myself.

Photo Credit

Installation View, 'I Think You Like Me But I’ve Been Wrong About These Things Before,' Natasha Matila-Smith, Artspace Aotearoa, 2021. Image courtesy of Sam Hartnett.

Photo Credit

Installation View, 'I Think You Like Me But I’ve Been Wrong About These Things Before,' Natasha Matila-Smith, Artspace Aotearoa, 2021. Image courtesy of Sam Hartnett.

Matila-Smith is a millennial; her self-revelations are seamless, easy to read for an audience weaned on oversharing. Unlike Sophie Calle, she came of age in a world where privacy was already under siege.

WHEN I THINK OF MATILA-SMITH’S WORK, I think of Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998)—the Young British Artist’s actual bed, unmade, post-depressive episode, presented in the gallery with an impersonal piece of blue carpet and sundry personal artefacts and detritus. The work is a touchstone for sad girls everywhere. Here I am, it says. Here is my dead skin, stains I made, condoms that were inside of me, fabric worn against my crotch for too many days, the cigarettes I smoked and the bottles of booze from which I drank, the pills I took to rearrange my hormones. Here’s where I’ve been hiding. Here’s where I return at night.

Following its exhibition at Tate Gallery in 1999 as one of the Turner Prize’s shortlisted works, My Bed incited much vitriol for its perceived excesses. It was intimacy in overdrive, too-much-information manifested in physical form. To critics like Adrian Searle, it was somehow disgusting and boring. In his review of the Turner Prize exhibition in the Guardian, he dubbed it ‘an endlessly solipsistic, self-regarding homage.’ What Emin had done so well, and what Searle recognised in his otherwise blinkered rant, was to undermine, irrevocably, the rules of the gallery as public by using it to reveal some of the lowest points of her private life through their overlooked accoutrements. In doing so, My Bed anticipated intimacy—and its violation—as a primary concern for artistic and philosophical thought in the early internet age.

To say Matila-Smith reveals the instability of ‘public’ and ‘private’ as discrete realms is not quite right, at least not for anyone under the age of forty. In 2021—when we’ve forgotten how to be anything but voyeurs, when we anticipate, enable even, the voyeurism of others, when we offer ourselves up as objects to be looked at, surveilled—what unbroken rules of private life could Matila-Smith’s work possibly break? The answer seems to be none. But the artist is less concerned with grandiose divulgences. She releases information slowly, a dripping tap of minute disclosures more likely to elicit dismissal than disdain. Like autofiction, literary disclosure’s genre par excellence, Matila-Smith’s work gives the impression of revelation just by virtue of its form, but the balance of autobiography and fiction remains a mystery. The artist appears to be the subject of her own work, a Narcissus-as-muse, but to what extent, we never know for sure.

Therein lies the tension: in her work, Matila-Smith appears vulnerable by choice. In fact, she sometimes appears too vulnerable, and that’s when suspicion arises, when we question what is real and what is, if not false, exaggerated for effect. Is Matila-Smith really a sad girl, or is she playing the sad girl? To which one could add, are sad girls online usually sad girls in the physical world, or is the sad girl a uniquely networked creature, made of text and image rather than flesh and blood?

Photo Credit

Installation View, 'In the Flesh,' Natasha Matila-Smith, Blue Oyster Art Project Space, 2017. Image courtesy of Blue Oyster Art Project Space.

Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1999)—the Young British Artist’s actual bed, unmade, post-depressive episode, presented in the gallery is a touchstone for sad girls everywhere. Here I am, it says. Here’s where I’ve been hiding. Here’s where I return at night.

WHEN I THINK OF MATILA-SMITH’S WORK, I think of Andy Warhol and his diaries, which record the minutiae of his beloved telephone calls. I think of his struggle with intimacy, his awkwardness, his love of machines, like the telephone and the camera, both of which made social interaction far more palatable. On Warhol, the novelist and critic Olivia Laing writes:

In this, as in so many things, he was the herald of our own era. His attachment prefigures our rapturous, narcissistic fixation with phones and computers; the enormous devolution of our emotional and practical lives to technological apparatuses of one kind or another.

Among many others, theorists Lauren Berlant and Melissa Gregg have explored the role networked technologies have played in dissolving the boundaries between public and private life, considering how our political, professional, and sexual selves have been affected by these changes. Indeed, Berlant’s assertion that it is difficult to ‘adjudicate the norms of a public world when it is also an intimate one’ holds particularly true when private forms of intimacy are confronted and made explicit. This is what happens when My Bed is in the gallery, and when sad girls take to the internet to share their selfies and their feelings, and again when Matila-Smith takes her selfies and her feelings back from the internet and into the gallery.

Photo Credit

Installation View, 'I Think You Like Me But I’ve Been Wrong About These Things Before,' Natasha Matila-Smith, Artspace Aotearoa, 2021. Image courtesy of Sam Hartnett.

For Berlant, desire names the process of longing for something, from which one usually hopes to gain comfort or pleasure. In her view, the object of contemporary desire is almost always intimacy—a life that is not only shared but one which is characterised by stability, comfort, and familiarity. Matila-Smith’s selfies and sad-girl slogans embody Berlant’s claim. They say, It’s logistically impossible for there to be someone for everyone, right?—and we feel the hint of desperation, the unwritten: please tell me I’m wrong.

How is intimacy altered by Matila-Smith recreating her bedroom in the gallery, not bringing her unmade bed into the space as Emin did, but curating a glossier version of her private space inside a public one? Is it more revealing to lie for eight hours in someone else’s sheets, or to walk through a gallery that is the artist’s bedroom as it would appear in a film of their life? As a bedroom work in a trajectory of bedroom works, is the shock of Matila-Smith’s latest exhibition that it is not so shocking at all to stand inside someone else’s private life and feel perfectly comfortable with that?

When I think of Matila-Smith’s work, I think about my own bedroom selfies, the ones I’ve taken just because I’m bored. I think about Berlant’s statement that ‘intimacy builds worlds; it creates spaces and usurps places meant for other kinds of relation’ and how I believe this means intimacy has transformative potential. I think about how Matila-Smith is harnessing this potential, challenging the prejudices within intimacy, pulling at their edges and pouring out her heart.

Photo Credit

Installation View, 'I Think You Like Me But I’ve Been Wrong About These Things Before,' Natasha Matila-Smith, Artspace Aotearoa, 2021. Image courtesy of Sam Hartnett.

About the Author

Lucinda Bennett is a Tāmaki-based writer published across numerous print and online platforms, including Artforum and Art New Zealand. She holds an MA with First Class Honours in art history from the University of Auckland and was previously Visual Arts Editor at The Pantograph Punch. Alongside her writing work Lucinda teaches art history and English at Avondale College.

You can find her on Instagram and Twitter.

ArtNow Essays is independently commissioned by the editor. The views expressed on ArtNow Essays are the authors' and are not necessarily held by ArtNow.NZ, the commissioning editor, editorial advisory, participating galleries, APGDN, or Creative New Zealand. While this platform does not publish readers’ comments, constructive feedback is welcome. Send your feedback to essays@artnow.nz.