TERMS OF ART NOW

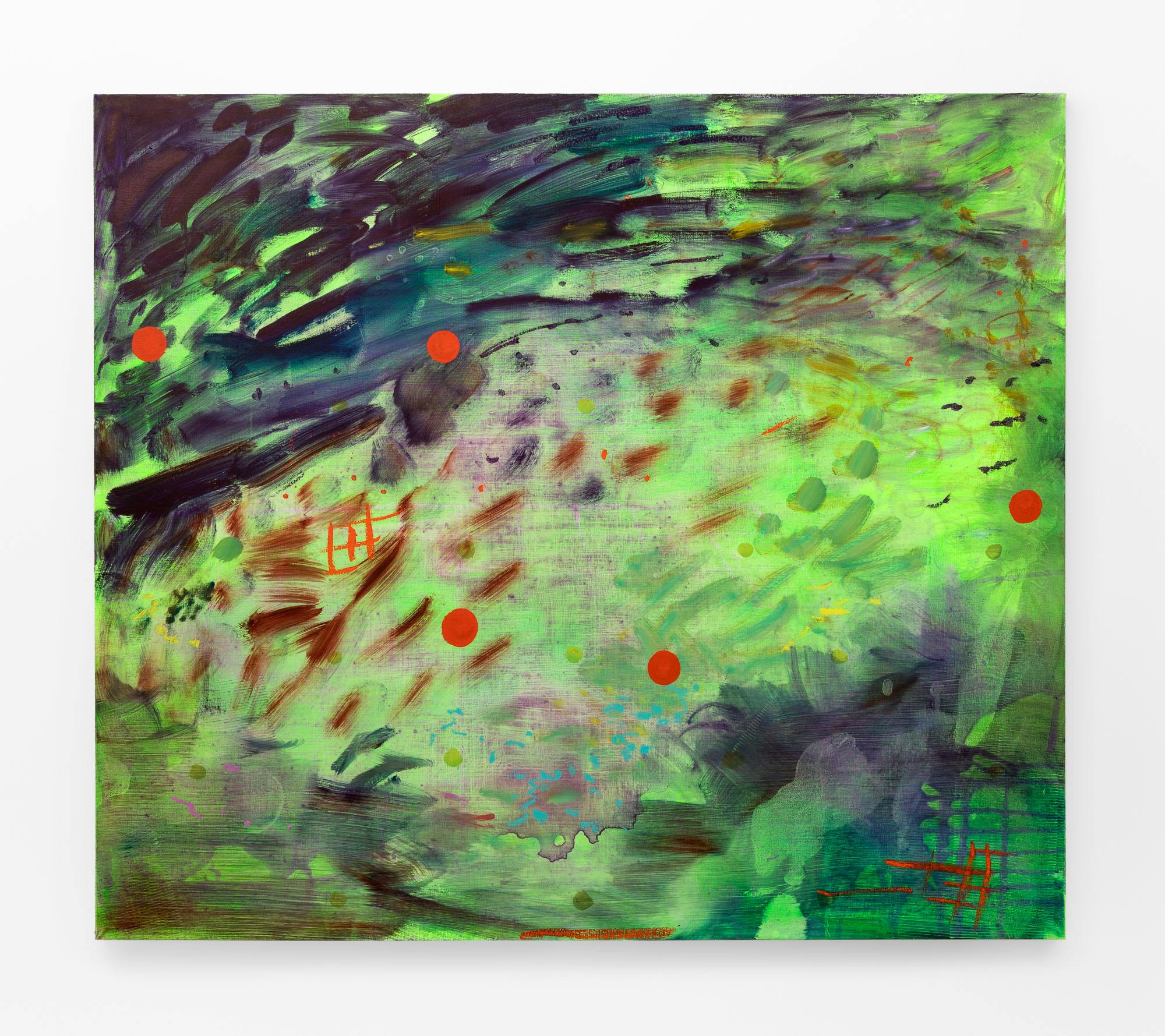

Photo Credit

Daniel John Corbett Sanders, ‘Urban Nothing,' 2021. Image courtesy of the artist.

ON THE ESSAY, Elizabeth Hardwick once said, ‘it is nothing less than the reflection of all there is.’ The critic, essayist, and novelist writing in 1986 for the New York Times characterised the form, with her usual finesse, as ‘just thought itself in orbit,’ glossing its fugitive and digressive character, its mercurialness. ‘The essay is diverse and several—it teems,’ Brian Dillon wrote thirty years after Hardwick, who is something of an exemplar for his own limpid prose. In Essayism, his fragmentary book of vignettes touching on sundry topics, among them style, lists, and biography, Dillon extols the ‘capaciousness’ and ‘variety’ of the essay form—neither of which, he reminds us, entails formlessness. He goes on: ‘Imagine a type of writing so hard to define its very name should be something like: an effort, an attempt, a trial. Surmise or hazard, followed likely by failure.’ The essay, then, is well-placed as a vehicle for the divergent dispositions and attitudes a writer might assume towards a work of art and its maker; it’s an ideal form for the unruly and mercurial subject, such as both are prone to being. And so the instigators of ArtNow Essays have chosen to install it as the site’s cornerstone.

This is no home for the exhibition review, a form that is too often single-minded, plodding, and dutiful in its balancing of claim and counterclaim. Like the press release, it can so often be formulaic. Instead a critical outlook on the conditions of art’s production, exhibition, and reception is paramount, but not to uphold some false claim to dispassion or any pretension to impartiality. This is an approach supported by an eight-person advisory committee comprising museum and gallery directors, curators, and writers from across the country who also advise on matters of sensitivity and help to sharpen and broaden the scope of commissioned texts. They, too, in spite (or because) of their various institutional affiliations, will ensure ArtNow Essays remains independent and unbeholden to any single museum, gallery, or publisher.

The essay, then, is well-placed as a vehicle for the divergent dispositions and attitudes a writer might assume towards a work of art and its maker; it’s an ideal form for the unruly and mercurial subject, such as both are prone to being.

Photo Credit

Installation view, Sione Tuívailala Monū presented by May Fair, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist and May Fair Art Fair. Booth render by Edward Smith.

LAST YEAR SAW AN EXHIBITION OF FLAGS so optimally pitched, so fine-tuned to elicit rancour. (1) Its aim, presumably, was to shake the credulous and pious purveyors of ‘identity’ for whom calls for freedom of expression had supposedly not made a mark. (The sophistry of a certain British scholar now persona non grata in much of the UK art world was enlisted to lend intellectual weight to the whole depraved affair.) The moment had arrived to enlighten on the perils of ‘tribalism’ but so much of the audience was supposedly unprepared to really understand what was at stake, morally and aesthetically; the subtleties of the flag and its crude semiotics had been glossed but they were still being misunderstood, perhaps wilfully, the instigators argued. And so the melee raged on with pieties, whose hatches had been battened down, remaining largely intact.

For the skeptical onlookers for whom the stakes were negligible, it was tempting to drape over this exhibition a one-size-fits-all cloak of plausible deniability: “But they were only trying to defend artistic freedoms.” Except the outlines of that instigating cohort’s long brewing intention to inflame could still be made out underneath. As for the less circumspect, those determined to attach themselves to this incendiary exhibition’s cause, it was the actions of the ‘great baying hordes’—and not those of the self-styled agitators—that were polluted by bad faith, self-interest, and opportunism. Culture in certain segments of the Left, the exhibition’s sympathisers argued, is poisoned by a wellspring of bile disguised as virtuous defence—as if a genuine grievance and resentment nullify each other, as if the latter undermines the structural asymmetries that have long beset many whose emblems were maligned alongside those of the truly nefarious.

Its aim, presumably, was to shake the credulous and pious purveyors of identity for whom clarion calls for free expression and nonconformity had supposedly not made a mark.

IN THE FLAG FIASCO old poses were struck in new clothes. There may have been a short lived air of novelty for some but many recognised the reactionary tune to which that exhibition moved. Shopworn strategies of formalist caricature (‘a flag, is a flag, is a flag’); ahistorical claims and false equivalences peddled as science (‘From a scientific standpoint, a flag, any flag, is nothing, just a scrap of cloth. In this sense, then, flags are silly’); and a general contempt for the necessary collectivism of the disempowered here masked as a principled disregard for conformity. It must surely take a great deal of effort to deny material realities and insist on an already-existing right to free expression that is evenly distributed, as if by some miracle, in a world of such startling inequality. (2)

But some of the old guard, who ought to know better, sprang to the exhibition’s defence, revealing how the fault lines weren’t simply generational. Among its sympathisers was EyeContact, a once-lively avenue for ‘spirited discussion on art and visual culture in Aotearoa New Zealand’. Now that several artists have withdrawn images of their work, and many others are likely to withhold theirs in future on account of the site’s defence of the flag exhibition, will this mark its denouement or a shift in direction? The decline of its contribution to the nation’s art scenes has been gradual, like a house perched atop the slow-eroding hill of art worlds past.

To be sure, the erosion of once-sturdy foundations has not been limited to the world of art criticism alone. There is, of course, atop a more stately hill, an even grander house—one whose colonial demons are proving difficult to exorcise. If recent media reports are anything to go by, it appears Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki might be keeling over, struggling to find its way as a responsive and responsible partner to Māori. Like its neighbour, the country’s highest ranking university, it’s an institution so often beleaguered by reactionary impulses. These impulses may from time to time be lent new faces and new names—modishly upgraded veneers—and even a new parlance hip to the inclusion and diversity game yet these institutions rarely veer from the hierarchy and paternalism at the heart of so many establishments of that scale.

It must surely take a great deal of effort to deny material realities and insist on an already-existing right to free expression that is evenly distributed, as if by some miracle, in a world of such startling inequality.

Photo Credit

Ammon Ngakuru, 'Evergreen (detail),' 2021, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs.

YET AMID ALL OF THIS CHAOS much is being created, and so much of it in pursuit of alternatives to the grand institutions. There’s a new guard on the horizon, some here already and others soon-to-arrive: a working group and forum for critical discussion on contemporary art; an artist-run space worthy of the epithet ‘queer’ (at least what the term once promised before it hardened into an empty ornament for embellishing corporate interests); an Indigenous art collective of international scale and ambition; a purveyor of affordable art and craft celebrating Moana nui a Kiwa; a much-anticipated contemporary art gallery for Māori by Māori; an online art fair re-fashioning old models and championing early career artists and writers; a new art magazine with international distribution (full disclosure: I’m guest co-editing a forthcoming issue); some things too protean and too renegade, others too nascent to fall neatly under a single rubric. Then there’s the return of a familiar title, now lushly revamped and operated by the brilliant minds who helm its creative output. Against this backdrop of new and vital art-making and writing, ArtNow Essays has emerged to signal the promise of these ventures and several others whose output is deserving of our attention.

Photo Credit

Emma McIntyre, 'The problem of vivacity,' 2020, oil, oil stick and acrylic on linen. Image courtesy of the artist. Image by Paul Forney.

So what to expect in the coming months? As inaugural editor of essays for ArtNow, I plan to direct at least some of my attention towards the literary-intellectual tradition of longform essays on publications, with the aim of cultivating a culture of informed and original commentary on contemporary art publishing in Aotearoa. Like other essays, commissions responding to artists’ books and exhibition catalogues will remain attentive to the potential of the essay form, drawing readily from journalism, criticism, memoir. On art and exhibition-making expect, among others, an essay by Andrew Berardini on the practice of Los Angeles-based painter Emma McIntyre; Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua on Kate Newby’s recent work; Matariki Williams (Tūhoe, Ngāti Hauiti, Taranaki, Ngāti Whakaue) on Indigenous internationalisms and the making of counter-canons; Francis McWhannell on Grant Lingard; an essay on recent developments in museology and repatriation; and a look at the work of Giovanni Intra including a forthcoming collection of his writing, Clinic of Phantasms (2022). Above all, the contributors to ArtNow Essays will share insights into what catches the eye and snags the conscience, what delights and rankles, asking always what purchase, if any, the work in question has on the present—that is, what it might tell us about the terms of art now.

Endnotes

(1) The exhibition in question, ‘People of Colour’ (2020), was staged by Mercy Pictures and accompanied by a commissioned essay from Nina Power.

(2) As Jon Bywater argues in his essay on the flag fiasco, what Mercy Pictures and their supporters insist on is ‘the abstract principle of “free speech” in the face of conditions that mean its exercise comes at others’ expense.’

About the Author

Tendai Mutambu is the inaugural commissioning editor for Art Now Essays.

ArtNow Essays is independently commissioned by the editor. The views expressed on ArtNow Essays are the authors' and are not necessarily held by ArtNow.NZ, the commissioning editor, editorial advisory, participating galleries, APGDN, or Creative New Zealand. While this platform does not publish readers’ comments, constructive feedback is welcome. Send your feedback to essays@artnow.nz.