Through a window into a time not my own

Photo Credit

Ana Iti, 'A dusty handrail on the track', 2021, still.

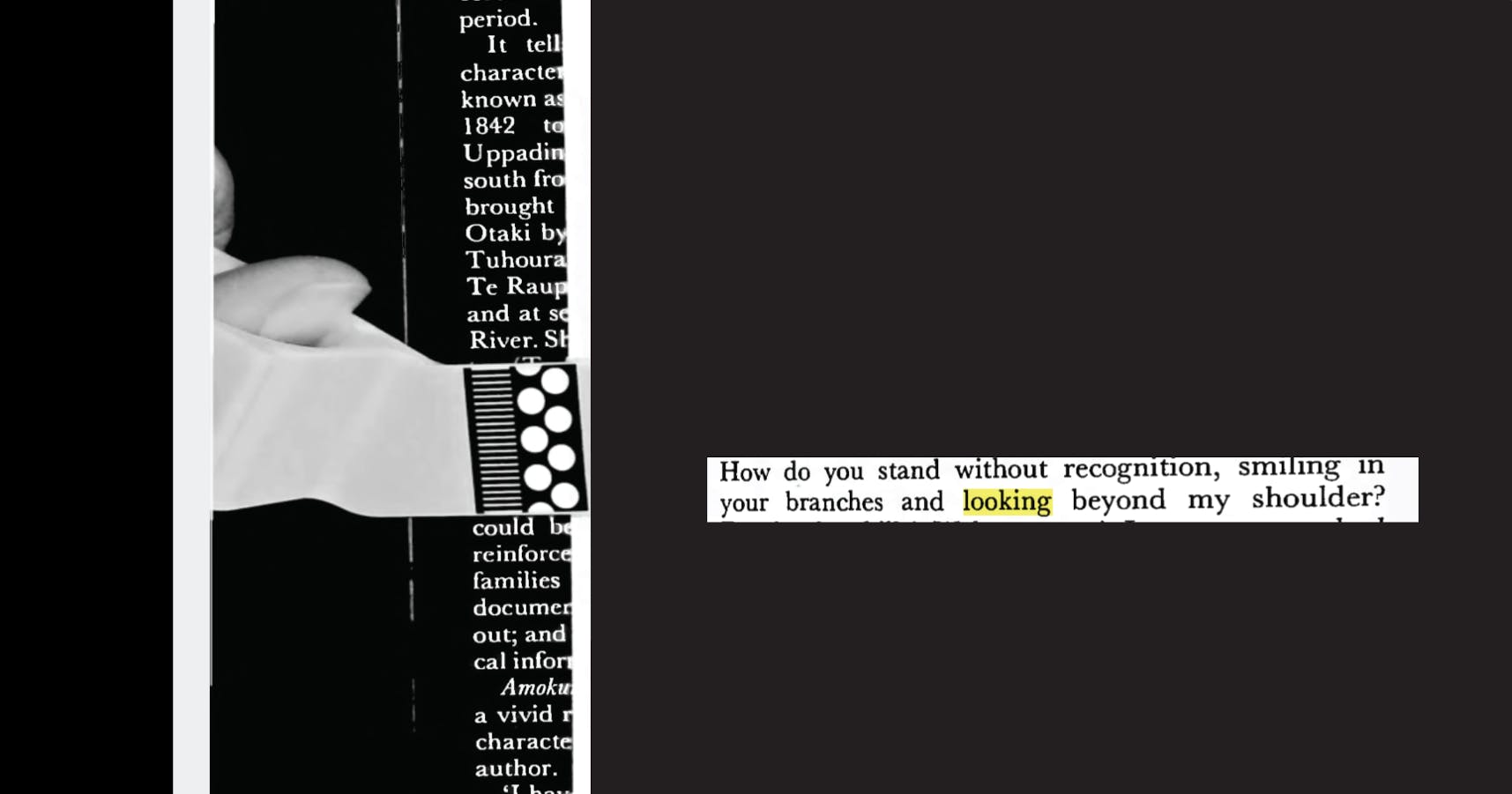

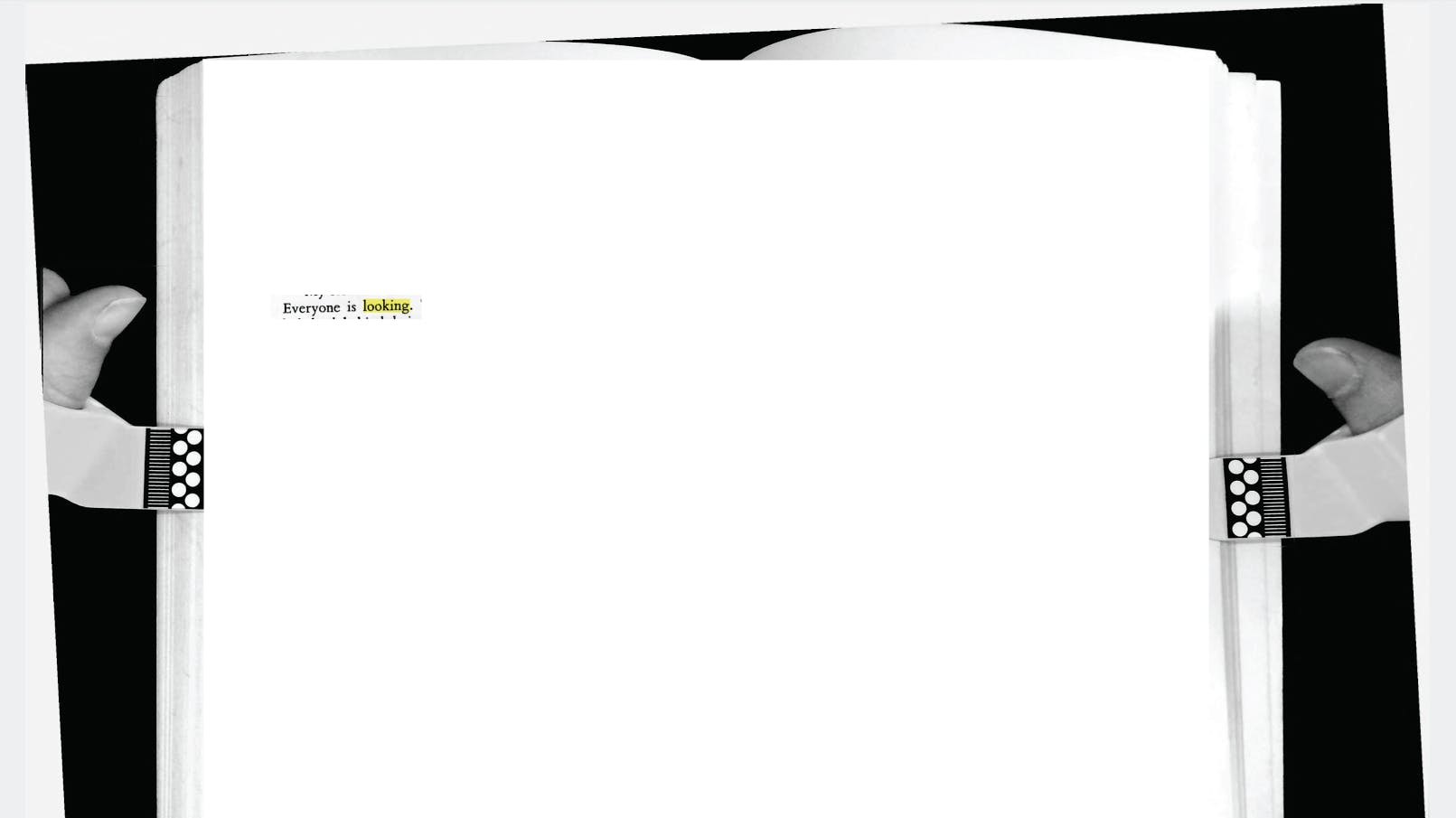

THROUGH THE WINDOW of my computer screen, where time and space collapse into data and pixels, is my only way out into the world of art. Through my screen and into artworks meant for other kinds of screens, I watch ‘A dusty handrail on the track’ (2021), a ten-minute, blackout poem of found phrases. The moving-image work, by Ana Iti (Te Rarawa), consists of scans made on a CZUR Shine Ultra scanner, of what looks like a novel. Throughout the work’s duration one scan transitions into another, like pages turning, only most of their words have been obscured. What we have left are phrases hinging on highlighted words: ‘looking,’ ‘path,’ ‘search,’ ‘track,’ ‘trying,’ ‘waiting,’ ‘undo,’ ‘progress’. These words, and the sentences built around them, combine to create the work’s puzzling narrative.

'A dusty handrail on the track' is the culmination of Iti’s McCahon House Artists’ Residency from July to September last year, during which she focused on two forms of literature: back issues of the reo Māori newspaper Te Pipiwharauroa: He Kupu Whakamarama (1899–1913) and the fiction of three wāhine Māori: June Mitchell’s Amokura (1978); Keri Hulme’s Te Kaihau: The Windeater (1986); and JC Sturm’s House of the Talking Cat (1983) (1). Iti’s research into the newspaper Te Pipiwharauroa gained prominence in a number of recent works including her CIRCUIT Artist Cinema Commission, ‘Howling out at a safe distance’ (2020). In the film she places, over the newspaper, a plain sheet of paper with long, narrow windows cut out for zeroing in on particular words or phrases. The same newspaper features in her billboard series for Te Tuhi, Kimihia te āhua (2020), which builds on the CIRCUIT commission, presenting her textual interventions in a number of public sites.

Photo Credit

Ana Iti, 'A dusty handrail on the track', 2021, still.

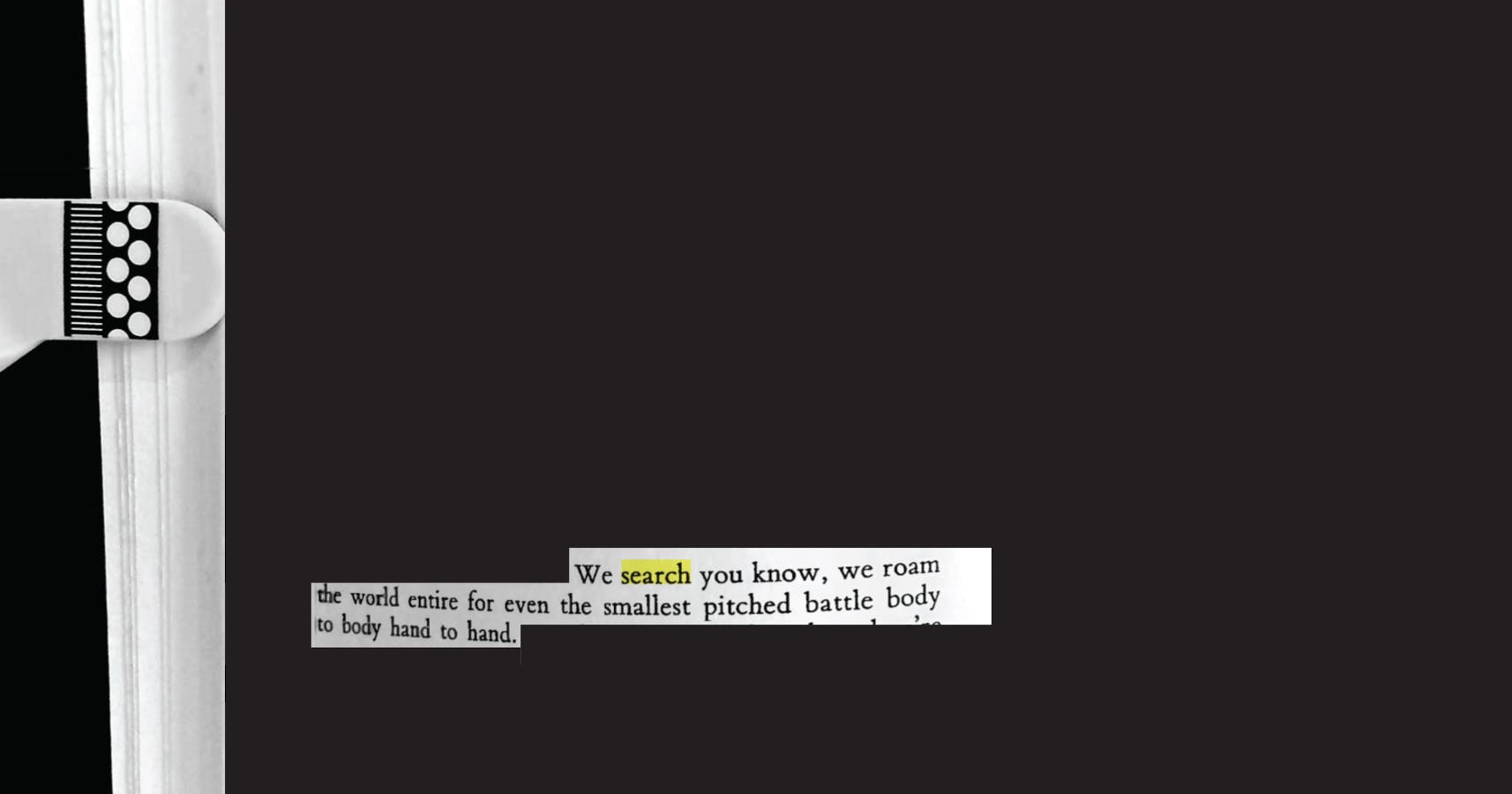

WHEN I ASK ITI ABOUT THE WORDS OF Hulme, Mitchell, and Sturm in ‘A dusty handrail on the track,’ she tells me:

When I am reading these books I find myself looking for something, some kind of connection between myself and the text as a … way to connect with the writer. The selection of words is an illustration of that feeling. I was also curious to see what something like 'searching' or 'waiting' looked like in [these writers’] voices.

The title alludes to how the work guides us on a narrative journey, offering a glimpse into fragments too small to give a sense of the original text. We are clearly being taken somewhere beyond the artist’s source material; looking, searching, waiting for something the details of which have been left unspecified. This is a figurative counterpoint to the literal paths Iti has taken her audiences along previously, as in her film, ‘like everywhere, words come one foot after another’ (2019), presented as part of an exhibition at the Dowse Art Museum in Te Whanganui-a-tara Wellington. Focused on a reconnection to whenua, Iti’s film takes its audience on a walk along a dirt path at night, the only light coming from behind the camera, perhaps a torch in the artist’s hand. ‘A dusty handrail,’ ‘Howling out at a safe distance,’ and ‘like everywhere,’ as Iti tells me, are ‘part of a related series about language and my relationship to it’.

Photo Credit

Ana Iti, 'A dusty handrail on the track', 2021, still.

We are clearly being taken somewhere beyond the artist’s source material; looking, searching, waiting for something the details of which have been left unspecified.

As we read the found phrases in Iti’s reconfigurations, there is a sense of looking through portals that collapse the time and space of the original authors, that of the artist documenting her acts of reading and editing, and ours as an audience viewing and reading on laptops, in galleries, on billboards. In the words of curator Abby Cunnane, writing on Iti’s work, reading the found texts can ‘continue to initiate relationships in the present’. In the most basic sense, that initiation occurs through the mere act of re-presenting these authors in the gallery. And through this act, new life is breathed back into their words and the authors are remembered, and read again, by people like me who want to know more about these words and ideas of ‘looking,’ ‘trying,’ and ‘waiting’.

At one stage in ‘A dusty handrail on the track’ the screen reads ‘“All right,” she said, not looking at him, and began walking back the way they had come.’ The line from JC Sturm’s short story ‘The Bankrupts’ reminds me of the proverb ‘ka mua, ka muri,’ which translates to ‘walking backwards into the future’. While walking backwards, or backwardness, in certain Western constructions of time, might be seen as undesirable, counterproductive, against the capitalist and modernist sense of progress, ‘ka mua, ka muri’ refers to a commonly shared understanding of time found in Indigenous cultures across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, the Pacific Ocean. It conceives of the future and the past as tethered and the past as something we must look to as a guide into the future. From within my own Indigenous Sāmoan context, the proverb reminds me of how ways of being that existed long before me should not only be valued but looked to as a way forward. This is a sentiment that feels apt in the context of Iti’s use of film to animate language and look back from her present.

Photo Credit

Installation View, 'Ka mua, ka muri', Shannon Te Ao, Te Uru, 2021. Image courtesy of Sam Hartnett.

From within my own Indigenous Sāmoan context, the proverb reminds me of how ways of being that existed long before me should not only be valued but looked to as a way forward. This is a sentiment that feels apt in the context of Iti’s use of film to animate language and look back from her present.

‘KA MUA, KA MURI’ IS A TWO-CHANNEL FILM by Shannon Te Ao (Ngāti Tūwharetoa) based on the road movie genre. Originally co-commissioned by Oakville Galleries, Toronto and Remai Modern, Saskatoon, it includes a song composed by scholar Kurt Komene (Te Ātiawa, Taranaki Whānui), with each of its channels featuring one of two sisters, played by Te Awhina Kaiwai-Wanikau and Waimarama Tapiata-Bright—both described as being ‘in the immediate wake of an unnamed tragic event.’ (2) The sisters each sing different verses of the song, at times alternately, like a call-and-response, at other points soaring into synchronous polyphony. My mind tracks back to my own experiences of car rides freighted by the unsaid, moments when mourning and melancholy cut to the bone, as the voices of Tapiata-Bright and Kaiwai-Wanikau do.

The film ‘Ka mua, ka muri’ accompanies a photographic series from the exhibition ‘Mā te wā’, previously shown at Mossman gallery. Mā te wā, commonly known to mean ‘see you later,’ might be read as a playful nod to the imminent closing of the private gallery which represented Te Ao, for which his photographic exhibition was a swansong. Or, more in line with Te Ao’s interest in time as a concept, mā te wā is used for its other, less common translations: ‘time will tell’ or ‘in time’. These photographs of a body in motion, frozen in a moment, have a shared origin with Te Ao’s film ‘Ka mua, ka muri’. They can be thought of as views from the same car window through which we catch blurred glimpses of the landscape passing by in black and white.

Photo Credit

Shannon Te Ao, 'Ka mua, ka muri', 2019, production still, two-channel video installation with sounds. Courtesy of the artist.

DURING HER McCAHON HOUSE ARTISTS’ RESIDENCY, Iti set herself the painstaking task of piecing together, word by word, using Google translate and an online Māori language dictionary, an English translation of recently purchased back issues of Te Pipiwharauroa: He Kupu Whakamarama—one of forty Māori language newspapers published by the East Coast church press. In contrast, Te Ao is known to collaborate on compositions and translations of te reo, in particular mōteatea—a word that describes a lament and the process of grieving—which similarly aligns with his collaboration with other experts including cinematographers. Yet despite these and other differences in their work—Iti’s often silent and literary; Te Ao’s often musical and cinematic—both spring from the simple desire to animate language and return it to the living.

‘The function of Māori language,’ Te Ao contends, ‘is to get to Māori ideas.’ And the language is, in turn, the perfect tool to get to those ideas in his work. What te reo Māori offers is a way of eliding histories and collapsing time, creating moments in which whole swathes of history are writ small into the nuances of words, phrases, idioms. On mōteatea, writer and curator Matariki Williams, a longtime interlocutor of Te Ao’s, writes that they are ‘written to respond to particular moments, but the ways in which they are performed, through chanting, singing, lamentations, transcends the circumstances in which they were written.’ This notion of transcending their own circumstances, their own limits and bounds, strikes me when I read the first line of the song: ‘Taapapa ana taku ara o te ora’ which translates to ‘The pathway of my life is laid out’. As with Iti’s literal and figurative paths, the opening lyric in Te Ao’s ‘Ka mua, ka muri’ points to a part of the question of searching in Iti’s work and answers it too.

Photo Credit

Installation View, 'Ka mua, ka muri', Shannon Te Ao, Te Uru, 2021. Image courtesy of Sam Hartnett.

What te reo Māori offers is a way of eliding histories and collapsing time, creating moments in which whole swathes of history are writ small into the nuances of words, phrases, idioms.

TO USE LANGUAGE IN TRANSLATION, in all its approximation to feeling and thought, is to accept—or resign oneself to—its limits while still trying to exceed them. It’s difficult for me not to think of this through my understanding of the Sāmoan notion of vā, and its relationship to space, time, relationality, the environment, the cosmos. It describes an Indigenous world in which we all have a place, and a time in which we are connected to our ancestors and those yet to come, joined in any given moment. I’ve tried many times to explain what vā feels like, or does to your body, in words that aren’t Sāmoan and I don’t know that I can. So I heed Te Ao’s words and remind myself that Sāmoan language gets to Sāmoan ideas. Yet language, whether written or sung, can allow for different ways and levels of understanding. It lets us in but never completely; it lets us peer through windows into worlds and times not our own. Ana Iti’s ‘A dusty handrail on the track’ and Shannon Te Ao’s ‘Ka mua, ka muri’ are works that bring the living force of language to my screen in those small windows of time when contact with art is granted, that is, until the next window opens.

Endnotes

(1) The work is currently exhibited as part of ‘How should we talk to one another?’ at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery.

(2) The work is currently exhibited as part of Ka mua, ka muri at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery.

ArtNow Essays is independently commissioned by the editor. The views expressed on ArtNow Essays are the authors' and are not necessarily held by ArtNow.NZ, the commissioning editor, editorial advisory, participating galleries, APGDN, or Creative New Zealand. While this platform does not publish readers’ comments, constructive feedback is welcome. Send your feedback to essays@artnow.nz.