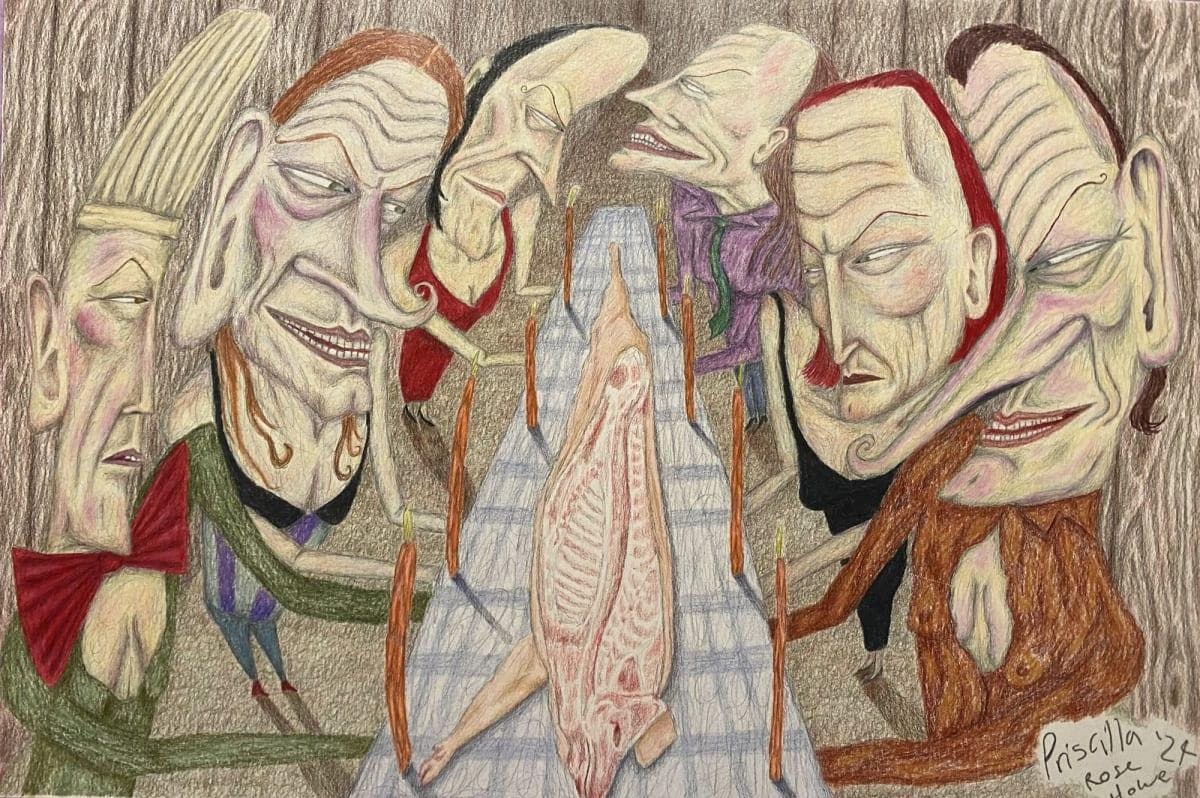

Priscilla Rose Howe, Celebration, 2025. Pencil on paper, framed.

Photo Credit

Priscilla Rose Howe, Celebration, 2025. Pencil on paper, framed.

Photo Credit

Priscilla Rose Howe’s drawings are obscene. They conjure a universe of apocalyptic pageantry, rendered in coloured pencil and oil pastel. Ribcages open like altars, meat floats like relics, and matriarchs leer over butchered pigs in domestic spaces — twisted into scenes of ritual and rupture.

Howe’s aesthetic is low-budget, high-intensity: part Troma gore, part John Waters camp. Her imagery distorts femininity, religiosity, and domesticity into grotesque theatre. The result is a kind of psychic autopsy: part shrine, part punchline. There’s no clean narrative here, no moral lesson, just ecstatic disorder.

Drawn in slow, scratchy pencil, these works are acts of both desecration and devotion. In Howe’s hands, the pencil becomes scalpel and wand, cutting and conjuring. Her figures are not whole, nor do they want to be. They sprawl, grin, ooze, and glow. The violence is visible, but so is the humour. Through absurdity and excess, Rabid seeks revelation.

This is mysticism by meat tray: a theology of the broken, the defiled, the divine. A lipstick smile. A halo of ribs. A sofa soaked in vomit and roses. The familiar becomes strange; the strange, sacred.

In a culture where repression and respectability often walk hand in hand, Howe’s work veers sideways. It rejects good taste, clarity, and control. Instead, it offers something unruly: a cracked kind of spirituality, where queerness, trauma, and laughter belong to the same ritual.

This text is adapted from Tuatua Soup by DJCS, an essay written to accompany the exhibition.

Priscilla Rose Howe’s drawings are obscene. They conjure a universe of apocalyptic pageantry, rendered in coloured pencil and oil pastel. Ribcages open like altars, meat floats like relics, and matriarchs leer over butchered pigs in domestic spaces — twisted into scenes of ritual and rupture.

Howe’s aesthetic is low-budget, high-intensity: part Troma gore, part John Waters camp. Her imagery distorts femininity, religiosity, and domesticity into grotesque theatre. The result is a kind of psychic autopsy: part shrine, part punchline. There’s no clean narrative here, no moral lesson, just ecstatic disorder.

Drawn in slow, scratchy pencil, these works are acts of both desecration and devotion. In Howe’s hands, the pencil becomes scalpel and wand, cutting and conjuring. Her figures are not whole, nor do they want to be. They sprawl, grin, ooze, and glow. The violence is visible, but so is the humour. Through absurdity and excess, Rabid seeks revelation.

This is mysticism by meat tray: a theology of the broken, the defiled, the divine. A lipstick smile. A halo of ribs. A sofa soaked in vomit and roses. The familiar becomes strange; the strange, sacred.

In a culture where repression and respectability often walk hand in hand, Howe’s work veers sideways. It rejects good taste, clarity, and control. Instead, it offers something unruly: a cracked kind of spirituality, where queerness, trauma, and laughter belong to the same ritual.

This text is adapted from Tuatua Soup by DJCS, an essay written to accompany the exhibition.