Please note, although the gallery is temporarily closed, the art is still there. Please address all enquiries to info@mossman.gallery

Mossman is pleased to present Acceptable Decoration, a group exhibition of work by Nick Austin, Fiona Connor, Bill Culbert, and Renee So.

Let’s start with Renee So’s two entangled wine glasses. Used as a symbol of fragility they are often found affixed to packing crates. They connote. They say be careful. They’re cracked already. They’re broken. The cracked wine glass says the content is fragile. That it can break irredeemably. It means top stow. Take extreme care. Now these symbols are rendered in wool. In a protective fabric. It’s oxymoronic. It’s a world upside down. More than that, the wine glasses have grown feet. They’re engaged in some sort of illicit tango. It’s the afterlife of objects. Their surplus animated. Better yet, why not say this very crack, this break in the glass, is the frisson of life, it’s a momentary turbulence that initiates the glasses. Those prosthetic legs enact a serpentine strategy of lively dynamism. This isn’t so much an animistic becoming as it is a kind of hallucination of surplus energy. That recto we can’t see, can’t glimpse, but know is there nonetheless.

This reserve, this shadow we can’t see, we know is everywhere and still we constantly probe at it. Take Fiona Connor’s notice board. This simple wooden board, whose patina is so pinpricked, so scuffed and marked. It merely hosts those poster reproductions, that sticker, that card for a taxi service. Is there not also a miscellany of pins, and staples and incidental mark-making. Surely this vernacular study is reserved as a nexus of information. Could we not say then, just as we said of Connor’s abandoned news stands, that this notice board is that reserve made dormant? Possibly even retired? Has it not been deliberately removed from circulation, dislocated, geographically, communally, and chronologically? Surely that’s the point then of this cessation of circulation, this termination of its role within a community. Could we not say then that the notice board has been abruptly brought to halt as an evidentiary scene, like those submerged villages of Pompeii or Tarawera? Could we not then also suggest that this notice board is like a reliquary, in that it too is removed from the source, but deliberately retentive? Perhaps there is another point. Take Connor’s more recent monochrome notice boards. Are these not now replicated so that they are divorced entirely of their social content. Have they not become a pure pictorial form, maybe even a pure sculptural form? And yet, are they not also a dense material that’s imprinted. Are they not 100% patina. It’s no longer just the reserve, it’s the surplus itself.

Speaking of surplus, let’s look at Bill Culbert’s Moa Point. Let’s presume that’s a reference to Wellington’s waste water facility, or at least a geographical locution to the flotsam of recycling that this battered suitcase reminds us of. But couldn’t we also say, that like Connor’s notice boards, Culbert’s suitcase also carries a patina, a residue of activity. Isn’t this even more likely precisely because the suitcase is so nostalgic (pre-castor wheels, pre-carryon)? And what of that fluorescent tube? Can’t we call that an arbitrator. Doesn’t it serve the same process as the bar in music does? Isn’t Culbert able to thread so many objects onto these bulbs precisely because they are a standardised unit? Is this not like Frank Stella’s enamel paint, the tin he simply dips his brush into? Could we not refer to Culbert’s fluorescent bulb as a similar kind of implementing device that transforms the artist into an executive agent? Take the line-up of plastic bottles in 'Blue, Red, Green, Blue, Yellow. This isn’t just decorative upcycling, but a kind of reductive use of surplus. Is this not why the title is so prescriptive. A subduing of the subject, so that it is not just threaded onto the light bulb, the standardised metre, but agglomerated as metonymic repetition that refers so simply to its own act of acquisition.

Again then the object reserves something of itself. It rears its head, not just as an instance of commodity surplus but as a retuned object whose afterlife escapes us. Is it possible then that Culbert’s fluorescent lights might serve the same function as the prosthetic legs of So’s wine glasses? That they animate the subject in concern. And yet, is this animation not just a hallucination of life, just our way of reckoning with a surplus that is never fully expressed, nor fully sated? No wonder we always haul up that immaterial wash, the social flow that courses through objects whenever we are so keen to talk about materiality. Should we not say then that an object only holds the possibility of inscription precisely because it is already a material enmeshed in the surplus? Perhaps there are lessons then that we can learn from Nick Austin’s two paintings, both from his 2018 Metaphysical Present series, which merely poses as an exhausted refrain on commodity culture.

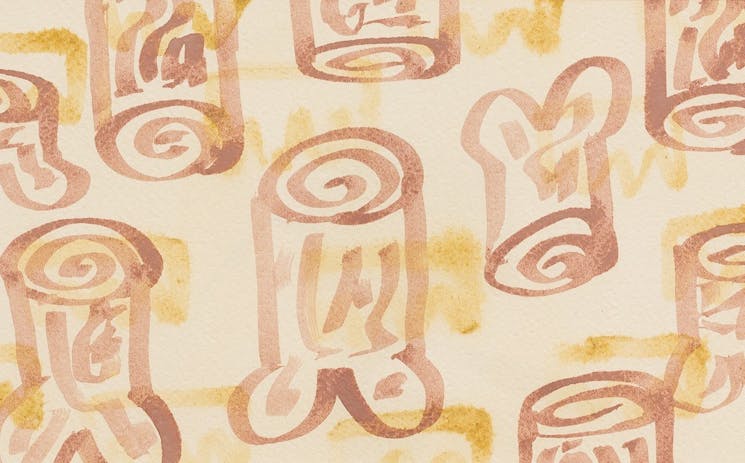

Could Austin’s mimetic Christmas paintings simply be a repetition of the Sisyphean routine of gift giving? And yet, doesn’t repetition lead to a kind of stasis, so that the object is always stuck, like the dormancy of Connor’s notice board, like the dormancy of Culbert’s plastic bottles? Perhaps it’s better then to take our cue here from the repetition, not of the gift, but the transitive image of the wrapping paper’s iconography, much as we did with So’s wine glasses? Take Austin’s rendition of the snowman with his green and yellow top hat and his green and yellow striped scarf. Does this image, which is continuously repeated inside a small polaroid-esque frame on a red background, not ooze with a deliberate mode of turbulence? Is the snowman’s scarf not aflutter? Is it not blowing vividly in the wind? Does snow not swirl about the purple sky? Surely that purple sky is the giveaway. It’s preternatural, it’s a conjuring trick. It’s total motion and total stasis. And yet the whole thing is repeated ad nausea, like the gifts themselves which repeat themselves, year on year, in slightly altered wrapping. Isn’t that the point of the other of Austin’s paintings, that repeating Christmas tree motif, one upside down, the next, right side up. Isn’t it all interchangeable and yet always diffuse, always shifting to the next phase, always in motion with or without our input. Does that not make us always-already somehow secondary? Isn’t that the point of Austin’s metaphysical rift, not as the obfuscation the fake gift might make it seem, but as the gift that keeps giving, one that can always be interchanged. Isn’t that the lesson of Acceptable Decoration, a title so misleading we know it to be more ambitious simply because of the decoy it poses.

–Hamish Win

Nick Austin (1979, New Zealand) lives and works in Dunedin. Recent exhibitions include: Console Whispers, Blue Oyster, Dunedin; Memory Disco, Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington; Classroom Newsletter, Ankles, Sydney; SOME VERMONT NATURE NOTES (1970) BY JOE BRAINARD, xxx, Dunedin; The Order of Things, Hocken Library, University of Otago; Poor Timing, Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; Paleo Apartments, Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland.

Fiona Connor (1981, New Zealand) is currently based in Los Angeles, U.S.A. Recent exhibitions include: In Plain Sight, Henry Art Gallery, Washington; Vienna Secession, Vienna; Celebration of Our Enemies: Selections from the Hammer Contemporary Collection, Hammer Contemporary, Los Angeles; Closed for installation, Sculpture Centre, New York; #10, Sydney, Sydney; Memory Disco, Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington; Community Notice Board (Cleaning Coop), Fine Arts, Sydney; Direct Address, 1301PE, Los Angeles.

Bill Culbert (1935 – 2019) lived between Croagnes, France and New Zealand. Recent exhibitions include: Desk Lamp, Crash, Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington; Time Tables, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; Colour Theory, Window Mobile, Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; Poor Timing, Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; Central Station, The Return, Andata Ritorino, Geneva; The Key to the Fields (with Andrew Barber), Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland.

Renee So (1974, Hong Kong) was raised in Melbourne, and now lives and works in London. Recent exhibitions include: Figurines, Mossman, Wellington; Transparent Things, Goldsmiths CCA, London; A distant relative, Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington; Renee So: Ancient and Modern, De La Warr Pavilion, East Sussex; Bootlegs and Ballarmines, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds; Idols, Freemantle Arts Centre, Perth; MEISENFLOO, Norma Mangione, Turin; The London Open 2018, Whitechapel Gallery, London.

Hamish Win is a graduate of the University of Canterbury. He completed his doctorate about lost pet posters in 2013. He is currently the baker at Baker Gramercy.

Opening Hours

- The gallery is temporarily closed but the art is still there

- Please address all enquiries to info@mossman.gallery

Address

- Level 2, 22 Garrett St

- Te Aro, Wellington, 6011

Please note, although the gallery is temporarily closed, the art is still there. Please address all enquiries to info@mossman.gallery

Mossman is pleased to present Acceptable Decoration, a group exhibition of work by Nick Austin, Fiona Connor, Bill Culbert, and Renee So.

Let’s start with Renee So’s two entangled wine glasses. Used as a symbol of fragility they are often found affixed to packing crates. They connote. They say be careful. They’re cracked already. They’re broken. The cracked wine glass says the content is fragile. That it can break irredeemably. It means top stow. Take extreme care. Now these symbols are rendered in wool. In a protective fabric. It’s oxymoronic. It’s a world upside down. More than that, the wine glasses have grown feet. They’re engaged in some sort of illicit tango. It’s the afterlife of objects. Their surplus animated. Better yet, why not say this very crack, this break in the glass, is the frisson of life, it’s a momentary turbulence that initiates the glasses. Those prosthetic legs enact a serpentine strategy of lively dynamism. This isn’t so much an animistic becoming as it is a kind of hallucination of surplus energy. That recto we can’t see, can’t glimpse, but know is there nonetheless.

This reserve, this shadow we can’t see, we know is everywhere and still we constantly probe at it. Take Fiona Connor’s notice board. This simple wooden board, whose patina is so pinpricked, so scuffed and marked. It merely hosts those poster reproductions, that sticker, that card for a taxi service. Is there not also a miscellany of pins, and staples and incidental mark-making. Surely this vernacular study is reserved as a nexus of information. Could we not say then, just as we said of Connor’s abandoned news stands, that this notice board is that reserve made dormant? Possibly even retired? Has it not been deliberately removed from circulation, dislocated, geographically, communally, and chronologically? Surely that’s the point then of this cessation of circulation, this termination of its role within a community. Could we not say then that the notice board has been abruptly brought to halt as an evidentiary scene, like those submerged villages of Pompeii or Tarawera? Could we not then also suggest that this notice board is like a reliquary, in that it too is removed from the source, but deliberately retentive? Perhaps there is another point. Take Connor’s more recent monochrome notice boards. Are these not now replicated so that they are divorced entirely of their social content. Have they not become a pure pictorial form, maybe even a pure sculptural form? And yet, are they not also a dense material that’s imprinted. Are they not 100% patina. It’s no longer just the reserve, it’s the surplus itself.

Speaking of surplus, let’s look at Bill Culbert’s Moa Point. Let’s presume that’s a reference to Wellington’s waste water facility, or at least a geographical locution to the flotsam of recycling that this battered suitcase reminds us of. But couldn’t we also say, that like Connor’s notice boards, Culbert’s suitcase also carries a patina, a residue of activity. Isn’t this even more likely precisely because the suitcase is so nostalgic (pre-castor wheels, pre-carryon)? And what of that fluorescent tube? Can’t we call that an arbitrator. Doesn’t it serve the same process as the bar in music does? Isn’t Culbert able to thread so many objects onto these bulbs precisely because they are a standardised unit? Is this not like Frank Stella’s enamel paint, the tin he simply dips his brush into? Could we not refer to Culbert’s fluorescent bulb as a similar kind of implementing device that transforms the artist into an executive agent? Take the line-up of plastic bottles in 'Blue, Red, Green, Blue, Yellow. This isn’t just decorative upcycling, but a kind of reductive use of surplus. Is this not why the title is so prescriptive. A subduing of the subject, so that it is not just threaded onto the light bulb, the standardised metre, but agglomerated as metonymic repetition that refers so simply to its own act of acquisition.

Again then the object reserves something of itself. It rears its head, not just as an instance of commodity surplus but as a retuned object whose afterlife escapes us. Is it possible then that Culbert’s fluorescent lights might serve the same function as the prosthetic legs of So’s wine glasses? That they animate the subject in concern. And yet, is this animation not just a hallucination of life, just our way of reckoning with a surplus that is never fully expressed, nor fully sated? No wonder we always haul up that immaterial wash, the social flow that courses through objects whenever we are so keen to talk about materiality. Should we not say then that an object only holds the possibility of inscription precisely because it is already a material enmeshed in the surplus? Perhaps there are lessons then that we can learn from Nick Austin’s two paintings, both from his 2018 Metaphysical Present series, which merely poses as an exhausted refrain on commodity culture.

Could Austin’s mimetic Christmas paintings simply be a repetition of the Sisyphean routine of gift giving? And yet, doesn’t repetition lead to a kind of stasis, so that the object is always stuck, like the dormancy of Connor’s notice board, like the dormancy of Culbert’s plastic bottles? Perhaps it’s better then to take our cue here from the repetition, not of the gift, but the transitive image of the wrapping paper’s iconography, much as we did with So’s wine glasses? Take Austin’s rendition of the snowman with his green and yellow top hat and his green and yellow striped scarf. Does this image, which is continuously repeated inside a small polaroid-esque frame on a red background, not ooze with a deliberate mode of turbulence? Is the snowman’s scarf not aflutter? Is it not blowing vividly in the wind? Does snow not swirl about the purple sky? Surely that purple sky is the giveaway. It’s preternatural, it’s a conjuring trick. It’s total motion and total stasis. And yet the whole thing is repeated ad nausea, like the gifts themselves which repeat themselves, year on year, in slightly altered wrapping. Isn’t that the point of the other of Austin’s paintings, that repeating Christmas tree motif, one upside down, the next, right side up. Isn’t it all interchangeable and yet always diffuse, always shifting to the next phase, always in motion with or without our input. Does that not make us always-already somehow secondary? Isn’t that the point of Austin’s metaphysical rift, not as the obfuscation the fake gift might make it seem, but as the gift that keeps giving, one that can always be interchanged. Isn’t that the lesson of Acceptable Decoration, a title so misleading we know it to be more ambitious simply because of the decoy it poses.

–Hamish Win

Nick Austin (1979, New Zealand) lives and works in Dunedin. Recent exhibitions include: Console Whispers, Blue Oyster, Dunedin; Memory Disco, Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington; Classroom Newsletter, Ankles, Sydney; SOME VERMONT NATURE NOTES (1970) BY JOE BRAINARD, xxx, Dunedin; The Order of Things, Hocken Library, University of Otago; Poor Timing, Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; Paleo Apartments, Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland.

Fiona Connor (1981, New Zealand) is currently based in Los Angeles, U.S.A. Recent exhibitions include: In Plain Sight, Henry Art Gallery, Washington; Vienna Secession, Vienna; Celebration of Our Enemies: Selections from the Hammer Contemporary Collection, Hammer Contemporary, Los Angeles; Closed for installation, Sculpture Centre, New York; #10, Sydney, Sydney; Memory Disco, Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington; Community Notice Board (Cleaning Coop), Fine Arts, Sydney; Direct Address, 1301PE, Los Angeles.

Bill Culbert (1935 – 2019) lived between Croagnes, France and New Zealand. Recent exhibitions include: Desk Lamp, Crash, Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington; Time Tables, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; Colour Theory, Window Mobile, Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; Poor Timing, Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; Central Station, The Return, Andata Ritorino, Geneva; The Key to the Fields (with Andrew Barber), Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland.

Renee So (1974, Hong Kong) was raised in Melbourne, and now lives and works in London. Recent exhibitions include: Figurines, Mossman, Wellington; Transparent Things, Goldsmiths CCA, London; A distant relative, Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington; Renee So: Ancient and Modern, De La Warr Pavilion, East Sussex; Bootlegs and Ballarmines, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds; Idols, Freemantle Arts Centre, Perth; MEISENFLOO, Norma Mangione, Turin; The London Open 2018, Whitechapel Gallery, London.

Hamish Win is a graduate of the University of Canterbury. He completed his doctorate about lost pet posters in 2013. He is currently the baker at Baker Gramercy.