Te Wharekura is an expression of the ahi-ka (burning fires) of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei (local tribe). The name Te Wharekura draws from tribal histories and refers to the traditional chiefly colour ‘kura’ (education) and establishes this whare (house) as a place of learning.

The building and its contents are a finely crafted waka huia (treasure box) for Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, tangata whenua (local tribe).

Housing a rich mix of physical and digital taonga toi (art works) and local indigenous histories, traditions and practices, it invites visitors to learn with the help of tribal members who are onsite.

Interactive digital technologies allow visitors to engage with a wide range of interpretive material to gain a deeper understanding of Tāmaki (Auckland) and its environmental challenges.

It holds physical and digital tribal taonga (treasures) and invites visitors to deepen their knowledge of environmental challenges facing Tāmaki and its waterways.

Te Wānanga (to gather together) is the public space that stitches together whenua (land) and moana (sea). It is a place for all to relax, come together, and celebrate Tāmaki (Auckland).

Contemporary Māori design and environmental thinking are embedded in the space. Coastal planting and marine species were reintroduced to reflect the original habitat.

Te Wānanga demonstrates kaitiakitanga (guardianship) and offers an exemplar of culture and nature successfully integrated into an urban space.

Macalister’s sculpture challenged preconceptions in the 1960s and sent revolutionary ripples through traditional art practices. She was the first female artist in New Zealand’s history to be commissioned to create a public sculpture. Macalister worked in a new way, for that time, engaging with tribal elders to ensure the work was culturally appropriate and reflected the wishes of iwi.

This monumental bronze statue of a dignified Māori man contrasted with the stereotypical image of a Māori warrior in a fighting pose. The result is a warrior clad in a prestigious kaitaka (fine cloak) of a rangatira (chief). He gazes skywards and holds a mere (traditional weapon), by his side in a peaceful stance.

Te Komititanga (to mix or to merge) is the city centre’s largest public square. The name reflects the mixing of people and the merging of waters.

It is where the Waitematā harbour and the Wai Horotiu stream (now running below the street) merged prior to land reclamation, and a welcoming space for people visiting the city by train, bus, ferry, and ship, with tens of thousands of people meeting, relaxing, and walking through it every day.

The square has 137,000 basalt pavers designed to incorporate mana whenua narratives and a whāriki (welcome mat) in a woven harakeke (flax) mat pattern.

In these steps Ko te Whāriki Whakatau Manuhiri / Ngā Whenu Mana Whenua is the woven design and the theme is of welcome. Each third strand references different tribal affiliations and different peoples - we are all part of the one mat. The border half circles indicate fish scales. The long lines represent the pursuit of excellence.

Ko ngā Puia o Tāmaki / Ngā Hau Wawara is the triangular and curved design, and its theme is the natural world. The larger triangles are Auckland’s volcanoes.

The design inside is tāniko (weaving) representing native fauna and flora and the curved motifs are the winds.

This ferry facility demonstrates the Māori concepts of manaakitanga (hospitality) and mīharo (awareness). Named by mana whenua, it compares the shape of the ferry berths to the bite of Horotiu one of the area’s traditional kaitiaki (guardians).

Sail motifs on the soffit represent the many waka (canoes) which plied the Waitematā Kupenga Rau (Waitemata Harbour). Kaitiaki (guardian) figures hold the piers to welcome and farewell users. A contemporary manaia (mythological figure), Te Wairere, runs along the wharf, affirming the connection of whenua (land) and moana (sea) and acknowledging those who have gone before.

Lighthouse was described by Anthony Byrt in ‘noted’ as a “gesture of permanent subterfuge in the heart of the property obsessed city”. Located on one of the most valuable and contested pieces of real estate in Auckland, The Lighthouse was a hotly debated public artwork. It is a full-size replica of a 1950s weatherboard state house.

Lighthouse honours New Zealand’s egalitarian past and is a beacon signalling Māori struggles for land retention. It questions the current and ongoing housing crisis, its impacts on Māori, and the way the country provides for its most vulnerable people.*

Sitting inside is a giant-scale stainless steel sculpture of Captain James Cook, the first European explorer to chart New Zealand (1769). Cook’s feet are not touching the ground as he did not set foot on Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland).

Surrounding Cook are clusters of neon lights, ‘chandeliers’ but not ones that hang from the ceiling but that represent the star constellations.

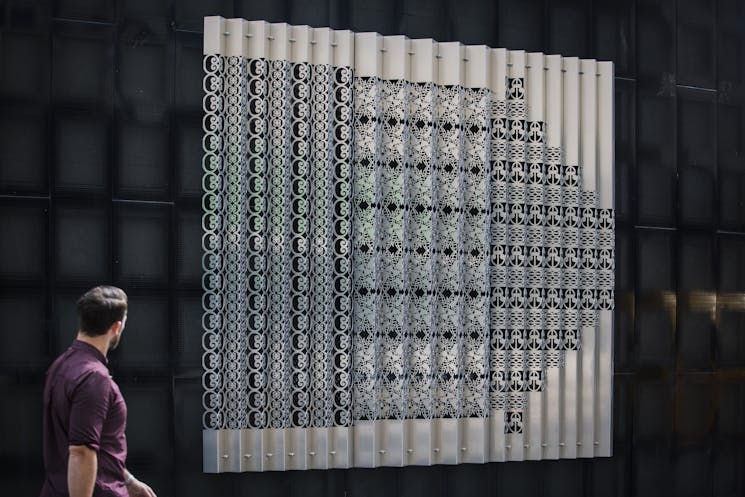

Hutchinson uses intricate patterns to tell stories of her ancestors. In this work, she references the Kāi Tahu creation story. It features not only Papatūānuku, the earth, and Takaroa, the progenitor of the oceans, but a third protagonist, Rakinui, who Papatūānuku had a relationship with while Takaroa was away. One panel in each of the two sets represents each of the three characters in the creation story.

Aroha ki te Ora was commissioned alongside Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art, an exhibition curated by Nigel Borrell (Pirirākau, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi, Te Whakatōhea).

Pou Tū Te Rangi means ‘the standing posts that reach for the heavens'. Pou are carved wooden posts traditionally used by Māori to mark territorial boundaries and places of significance.

Bailey uses these pou to celebrate the relationship between tāngata (people) and whenua (land) and to highlight the link between the ancestors, the environment and the mana (authority) of iwi (tribes). He explores key themes of te kotahitanga (unity), te piri tahi (uniting), and te mahi tahi (collaboration).

Pou Tū Te Rangi reflects Britomart’s past and present – its history as a significant place for early Māori, colonial and maritime activities, and a place where cultures and ethnicities converge.

Each pot bears the name of a different maunga (mountain) reinforcing the city’s role as a place where people from around the country gather.

Maunga was commissioned by the Britomart Arts Foundation in collaboration with Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki as part of the exhibition, Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art.

This square is named Takutai (seacoast or shoreline) and is on reclaimed land near Waitematā Train Station. Pipi (small shellfish) beds once flourished on this shoreline. Pipi and other kaimoana (seafood) were an important food source for early Māori living in the area.

Pipi Beds is made up of 16 sculptural stones which are part of the Ngāti Whātua Ahi Kā (burning fires) series of works. Steel pipi shells are embedded into the paving and 24 pop jets intermittently shoot water up from the ground. This represents the squirting action of shellfish as they filter water for oxygen and food before expelling it.

Bailey created five bronze sculptures of waka (canoes) for this site, named Tauranga Waka (the resting place of canoes). Their location marks the shoreline before reclamation began in 1860. The Beach Road site of the waka is 200 meters inland from the current shoreline. The earth used for the reclamation was taken between 1860 and 1880 from Tangihanga Pūkaea where Te Reuroa Pā once stood in nearby Waterloo Quadrant.

Bailey’s waka (canoes) emerge from the footpath as though they have been pulled up onto the beach. The waka prows are not as elaborately carved as waka taua (war canoes). This simpler style of carving is on waka used for fishing, collecting kaimoana (seafood) and transporting people and produce.

The six murals celebrate the deep connections of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei to the land, and its waters and their enduring presence in Tāmaki Makaurau.

Each one is imbued with symbolism, from the ancestral waka and guiding stars to the resilient kawau bird, a tīheru (bailer) speaking to the role that everyone has an important role and place no matter how insignificant they may seem. The waka being dragged into the light pays homage to the name of the precinct, Te Tōangaroa, and the majestic waharoa (entrance), (Te Pou Tākiri ki Tua pictured) welcomes the multitudes to its village.

The work is a contemporary representation of a hīnaki (eel trap). The tuna (eels) which were a great source of food for iwi (tribes). The design was inspired by the whakataukī (proverb) “Te pai me te whai rawa” which refers to the wealth of the iwi.

Tuna are associated with the awa (rivers) that flowed into Te Tōangaroa and the Waipapa fishing village. Hina symbolises both the wealth and abundance in Te Tōangaroa.

The poutokomanawa (central support pole) in whare rūnanga (meeting houses) symbolise ancestors that are significant to Māori. Here it recognises the enduring status and vibrancy of people of the Ngāti Whātua (tribal group) in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland).

The work is made up of pou (carved posts) and kōhatu (boulders). Inscribed on the boulders are the words ‘He kākano ahau i ruia mai i Rangiātea - I am a seed sown from Rangiātea’. This message emphasises the excellence of ancestors and reinforces the potential of their descendants.

The pou inside the arena and forecourt symbolise the continued occupation by descendants of the great pā (fortified villages) sites in Auckland.

By 2013, the 1930s pedestrian footbridge over Tāmaki Drive linking Taurarua Pā and the Parnell Baths needed to be replaced and raised to accommodate the electrification of Auckland’s rail network.

Nicholas designed a pūngarungaru (water ripples) pattern depicting the ebb and flow of water and the movement of people and traffic on and under the bridge. The designs are engraved into the concrete structure and the glass balustrade. Nicholas says the patterns, colour and texture are sensory taonga (treasures) symbols of a growing and evolving community.

This work references the whakataukī (proverb) ‘He iti te matakahi, pakaru rikiriki te tōtara - A wedge may be small, but it can fragment the tōtara’.

Standing at 3.6metres in height, the toki (adze) designed by Arekatera Maihi sits proudly at Taurarua, Judges Bay. it is a significant identity piece which marks the eastern border arm of the 3000 acres gifted by Apihai Te Kawau to Governor Hobson to establish Auckland City.

The material used to shape the toki is laser-cut corten steel and steel mesh, which was fabricated by Metal Magic, Hawkes Bay and installed by Decker Landscape and Civil, Auckland.